From Only Yesterday (1991) to Seven Samurai (1954), here are the greatest Japanese movies of all time.

With a rich history that spans over a hundred years, Japanese cinema has been one of the most influential and oldest sources of entertainment on celluloid. From the silent films inspired by Kabuki theatre in the early twentieth century, to modern Kaiju, Mecha and Anime films that delve deep into fantastical worlds of surreal imagination, Japanese cinema has something to offer to every cinephile. With an astounding oeuvre of work that straddles both realistic portrayals of day-to-day life as well as showcases certain esoteric influences of traditional Japanese culture, Japanese films have been monumental in shaping not just the discipline, but the industry of world cinema at large. Here’s a look at the best Japanese movies of all time.

Read: The Film That Ended A Career (Almost!)

25. Mr. Thank You (1936)

A grateful bus driver who is characterized by his utterances of gratitude on a narrow, mountain road is the eponymous protagonist of Mr. Thank You. The film, little over an hour, focuses on the relationships that the protagonist establishes with his passengers who he must drive to the nearest train station — grounding his experience in the accessible dynamics of community and travel, while navigating the ebb and flow of human interaction in a pre-World War II Japan caught between tradition and liberation. Director Hiroshi Shimizu, a crucial figure in the transition from silent cinema to sound films in Japan, is at the helm. What the film lacks in plot, it makes up for with its fascinating and immersive character studies of ordinary people leading ordinary lives.

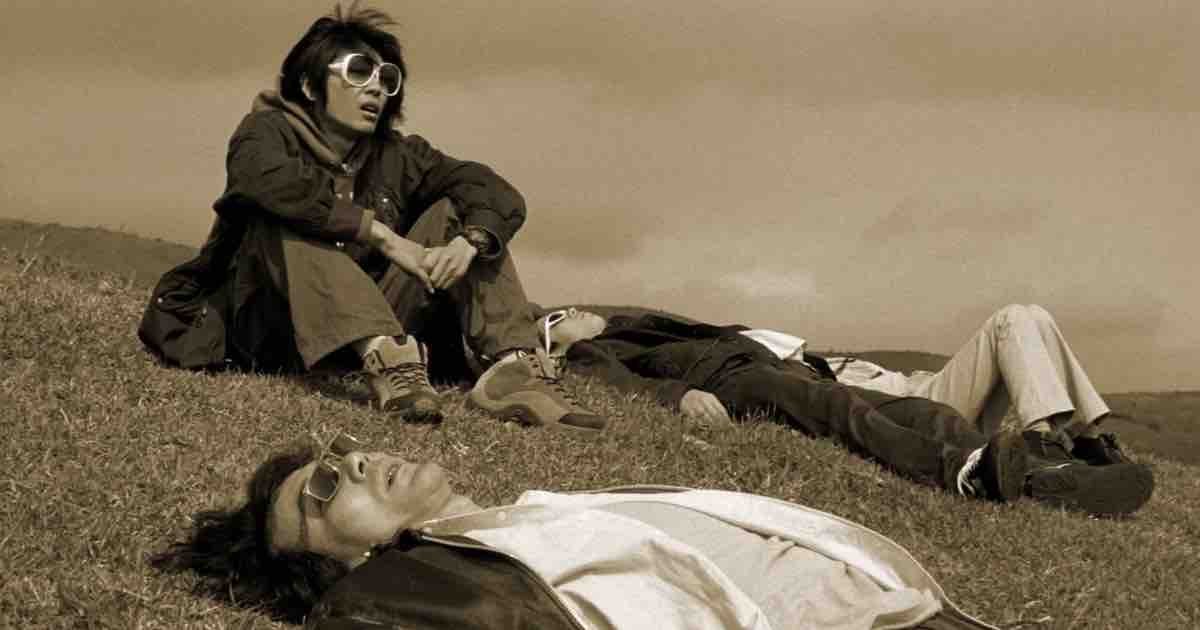

24. Eureka (2000)

Somewhere in rural Japan, a bus is violently hijacked by a gunman. Only three people survive this extremely traumatic event — bus driver Makoto, and teenage siblings Naoki and Kozue. While they’re unable to move ahead and live normal lives, circumstances and tragedies strike to bring them together once again. Nearing a runtime of nearly four hours, the film is a massive commitment. But it deftly utilizes storytelling, subtlety and color to not just narrate the events but make the audiences feel the full emotional heft of what is unfolding on screen. Come for the masterclass in subtly elegant storytelling, stay for the beautifully understated climax.

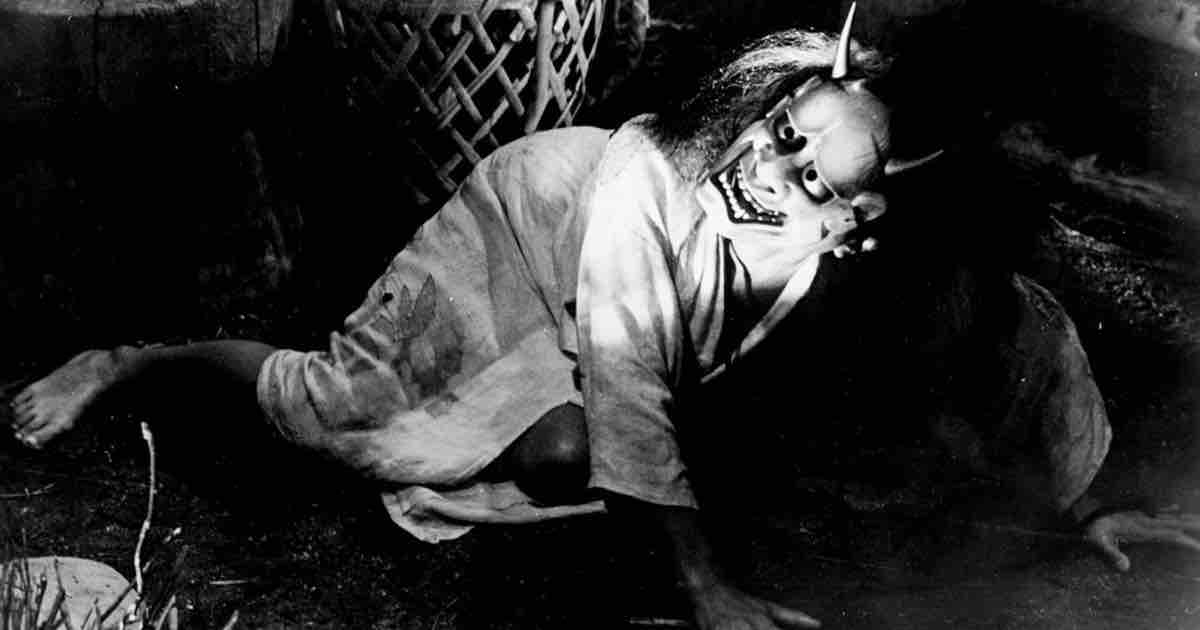

23. Onibaba (1964)

Japanese cinema is well renowned for its horror sub-genres; filmmakers have noted the use of elements borrowed from Japanese mythology — yurei, yokai and oni are common presences. Onibaba is one of the earliest and finest examples of the same. The title of the film translates to Demon Hag. Set in the mid-fourteenth century, the plot follows two women tied together in a macabre dance of envy, violence and sorrow. Having lost a significant presence in their life, two make a living stealing from soldiers. The true horror of the film relies upon psychological aspects, emotional turmoil and the mystery of the characters, rather than outright supernatural elements or jump scares.

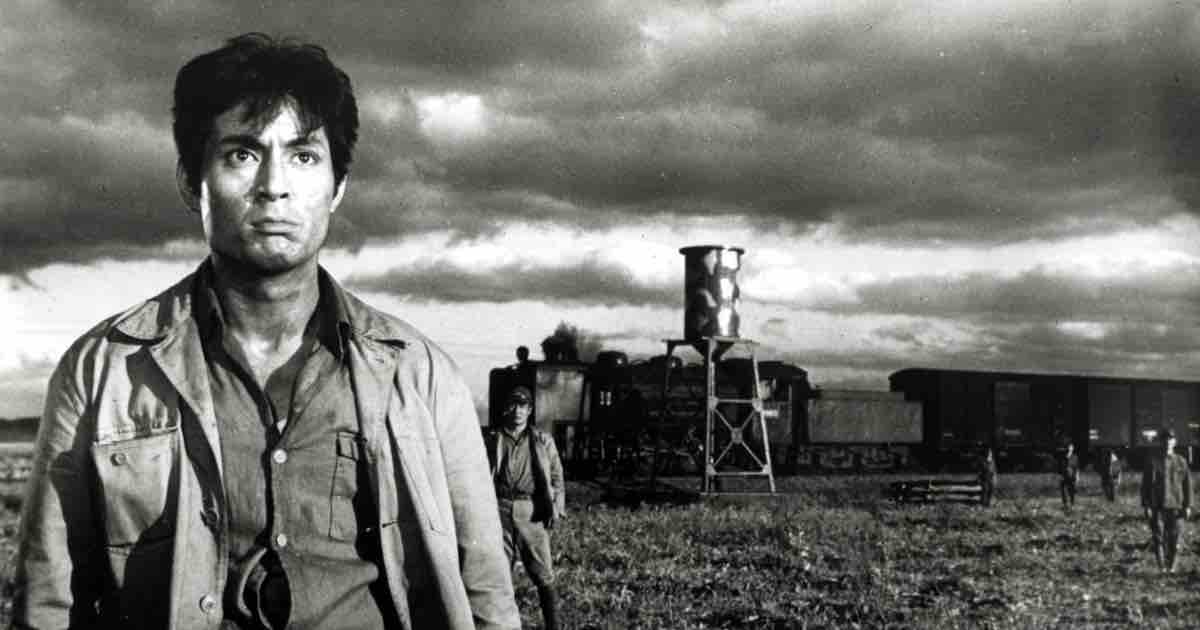

22. The Human Condition trilogy (1959-1961)

Masaki Kobayashi’s The Human Condition is a set of three Japanese epic movies that were inspired by a best-selling six-part novel. It showcases with extreme realism, the difficulties of a socialist pacifist in a totalitarian World War II world. The ideological conflicts coupled with the brutal background of the unrelenting war paints a clear picture of the horrors of war. While death and futility of war form some of the main elements, the film focuses more on individual corruption and dehumanisation, which makes it more than just a war trilogy and transcends to become an epic battle between humanity and the inhumane.

21. Love Exposure (2008)

Crossdressing, love triangles, religion and sexuality collide in this wacky tale of hijinks that most critics have described as sheer chaos and madness. The plot follows Yu Honda, a young teenager from a catholic family who is sucked into a world of petty crime and upskirt photos. However, things change when he meets a girl named Yoko and develops an alter ego that she falls in love with. Meanwhile, Yu himself has an admirer in Aya Koike, a cult member. Despite the film’s four-hour long runtime, there is never a dull moment. The plot is rife with offbeat humor and absurd drama with a distinct arthouse sensibility that stands out from most films in the genre of comedy/dramas.

20. Hana-bi/Fireworks (1997)

Hana Bi follows the story of an unemployed detective who is in hot water with the yakuza after borrowing some money to take care of his terminally ill wife, and is now unable to repay it. Things come to a head after the former law enforcer is forced to live a life of crime, and is chased down by his colleagues who are tied to him through tragic circumstances.

What makes the Japanese film worth watching is the slick crime-drama narrative, elements of noir, along with the purely stylistic adornments in the film, which make it more than just the sum of its parts. Director Takeshi Kitano, who also plays the protagonist, takes an approach to the violence in the film that strives to find calm even in moments of staggering distress.

19. My Neighbur Totoro (1988)

In many ways, Hayao Miyazaki has come to be associated with the very spirit of modern Japanese animation. The founder of Studio Ghibli, his approach towards animation styles and storytelling lends his films a timeless quality, and My Neighbur Totoro is no exception. Totoro is a friendly forest spirit who is befriended by two little girls, Satsuki and Mei. The siblings have just moved into a house in the woods. Totoro and many others like him abound in the adventures that follow.

Watch the film for the breathtaking animation that flawlessly blends the real and the fantastic, the adorable characters, and the many characteristics of Studio Ghibli films — a young child on the cusp of a life-changing event, friendly forest spirits (kami) and a whimsical, beautiful world that is both imaginary and intimate.

18. Only Yesterday (1991)

Summer, nostalgia and pineapples: three words perfectly set the mood for another Ghibli offering on this list. The film revolves around Taeko, a woman working in the city who goes to the rural area of Yamagata during summer holidays. Nostalgia and reminiscing about her adolescent days follow in this beautiful and heartwarming tale of childhood and wonder, as Taeko has many flashbacks about the small pleasures of youth. Only Yesterday blends and blurs time, interspersing flashbacks with the present. It’s bound to make you feel as fuzzy and snug as a warm summer evening.

17. Ran (1985)

Written and directed by the legendary Akira Kurosawa, Ran is an epic drama film that derives its plot loosely from Shakespeare’s King Lear. The conflict in the film steps from an aging warlord who is faced with the prospect of dividing his kingdom among his three sons. From this arises great betrayal, loss, tragedy and perfidy. It is noteworthy that this was one of Kurosawa’s last epics, and won the Academy Award for Best Costume Design. Spanning across genres, it is an epic drama, action film, tragedy and period film all at once.

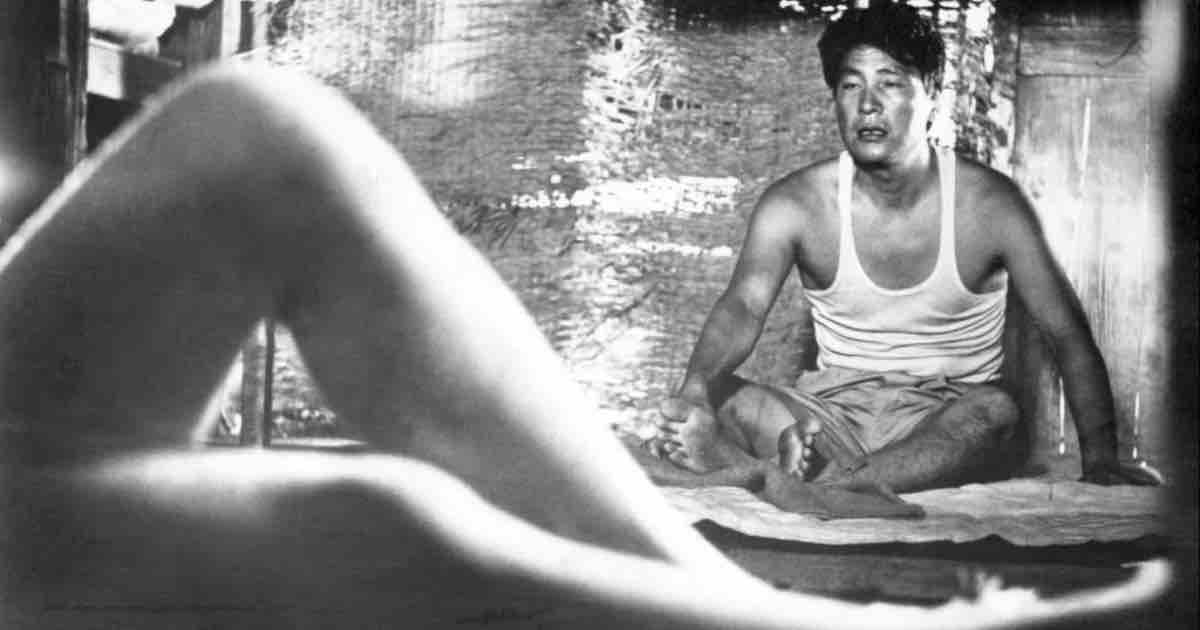

16. The Naked Island (1960)

With nearly no spoken dialogue, The Naked Island is a black and white film that depicts the lives of a small family on the island of Seto, with all of its hardships and suffering. Words are rendered unnecessary as the extraordinary plight of the family of four is brought to life using only visuals that are as heartbreaking as they are admirable. Director Kaneto Shindōinterestingly tells of an anecdote where he on purpose made actors carry heavy buckets of water so that the yokes they used appeared bent, to denote the incredible toil of the family.

15. Fires on the Plain (1959)

A war film set during World War II, Fires on the Plain recounts the story of a Japanese private as he struggles to make it out alive. While the director himself has noted the thematic balances of war and death, the film juxtaposes the twin principles of death in the form of war and tuberculosis that afflicts the protagonist, Tamura, against his fierce desire to stay alive. It’s worth noting that the film was directly inspired by the fallout from the atom bomb in Japan, with the director having witnessed it firsthand, and the film takes great care to paint a nuanced picture of the price and horrors of war.

14. Woman of The Dunes (1964)

With two Academy Awards nominations, Woman of The Dunes tells the story of Junpei, an entomologist, who is trapped in a village around the titular dunes in his search for rare insects. The film has to do with his repeated attempts at escape, and his subsequent failures. The minimalism, sparse plot, and blunt sound design, score and set design for the treacherous sand dunes of the film cement its place in the canon of a post-modern, avant garde cinema. The loose retelling of the myth of Sisyphus within the story has been noted by many as a metaphor for futility of existence and escapism from society.

13. Still Walking (2008)

Set over the span of a single day, the film follows a family, the Yokoyamas, as they come together to commemorate the death of the eldest son. As things start to unravel between them, old resentments and secrets come to the surface. Conceived by the director as a tribute to his late mother, the film represents the smaller moments in family life, denoting affection and conflict both through small gestures, especially in moments of the family coming together to cook and partake in meals. An extraordinary work that dives deep into family ties and the tensions underlying the same, it is sure to move you and pull at your heartstrings.

12. Princess Mononoke (1997)

When Ashitaka, the last prince of the mysterious Emishi clan is attacked and cursed by a dying boar god, he must travel far and wide to find a cure. However, this is further complicated by the people he meets on his journey — humans adamant upon cutting down the forests, San, a girl raised by wolves who wants to protect nature and the forests, and the Great Forest Spirit itself. This 90s anime is a beautiful story depicting complex ideas and positions on war, the environment and the conflict between nature and civilization. The film’s nuance comes from the idea that there are no true heroes or villains but simply people who are doing the best they can to get by.

11. A Page of Madness (1926)

Made in 1926 and considered a lost film for over four decades before its rediscovery in 1971, A Page of Madness has been described as a seminal work of Japanese avant-garde cinema. The silent film revolves around the janitor of a mental asylum who cares for his wife, an inmate of the same asylum. After being informed by his daughter of her impending marriage, his fantasies and realities begin to blur until it is no longer clear which is which. Watch this masterpiece for a mind-bending narrative structure and a new form of expression in cinema. In fact, the usage of masks, narration and dancing was emphasized to break away from the conventions of naturalism in cinema. Interestingly, the film was alternately named A Page Out of Order, reflecting the film’s disregard for linear storytelling.

10. High and Low (1963)

Akira Kurosawa’s High and Low is not only a stylishly made police procedural crime drama, it also features unexpected emotional heft and a fascinating portrait of envy. Gondo, a wealthy executive, is poised to take control of a lucrative shoe company when his chauffeur’s son is kidnapped, mistaken for Gondo’s own son, and he is backed into a corner to pay his ransom. Tense performances from a star-studded cast and a tightly plotted screenplay that rarely falters make it a must watch.

9. When A Woman Ascends The Stairs (1960)

Mikio Naruse’s 1960s drama features a widowed heroine who works as a hostess in a bar, and wants to open her own. Financial hardships, personal struggles and illness keep her from realizing her dream, as she still mourns her dead husband, and cannot let go. Like most Naruse’s films, it follows a common theme of the everyday lives of women of modest means, who do the best they can to survive in a harsh world. This tale of struggle and dignity in contrast to a newly materialistic Japan in the 1960s is bound to tug at your heartstrings.

8. Harakiri (1962)

Harakiri, or Seppuku, refers to the ritual of suicide through self-disembowelment undergone by samurais to restore honor to themselves or their families. Directed by Masaki Kobayashi, the film begins with the arrival of a ronin named Hanshiro, who requests permission to commit harakiri in the premises of the great Iyi clan. He is then insulted and told the story of the last samurai, Motome, who had arrived to commit harakiri in the same premises. It is now that Hanshiro reveals the ties between him and Motome, as well as the samurais who forced his death. This period film, or jidaigeki, unfold with the slow precision of a murder mystery and is frequently cited as one of the greatest samurai films ever made.

7. Death by Hanging (1968)

Nagisa Oshima’s Death by Hanging is an incredibly complex exploration of crime, violence, perversity and guilt. The protagonist is an unnamed Korean man named R who is to be hanged. However, when he survives the hanging but loses his memory, a conundrum is posed as to how to go about the case of a criminal who does not recall their crime and punishment. Renowned for its absurdity of narrative and techniques borrowed from Brecht, a German modernist theatre director and playwright, the film is a meditation upon the grey areas of innocence, guilt, reality and memory. Not only does the film handle these topics within a larger arena of race and ethnicity, it leaves open-ended questions for viewers to ponder upon.

6. An Autumn Afternoon (1962)

The iconic Yasujirō Ozu’s swansong, An Autumn Afternoon is the story of the Hirayama family, focusing particularly on the father, the widowed Shuhei Hirayama (played by frequent Ozu collaborator Chishu Ryu) who seeks a groom for his daughter. Hirayama’s friends from his time as a Naval Captain during World War II, his two sons and his unmarried daughter make up the dramatis personae of this sweet, understated film which takes a long, introspective look at age and loneliness without giving in to unnecessary sentimentality.

WATCH: 10 Greatest Yasujiro Ozu Films, Ranked

5. Sansho the Bailiff (1954)

Kenji Mizoguchi’s period drama, set in the Heian period of feudal Japan is the story of two children born into nobility who are estranged from their parents and sold into slavery to the titular Sansho. The siblings Zushio and Anju grow up in the slave camps and hatch a plan to find their mother, who they believe has been sold into prostitution. Based on an oral tale, the film is a moving testament to mercy, dignity and the human spirit. It is frequently included in Mizoguchi’s finest works.

4. Late Spring (1949)

Yet another Ozu masterpiece on the list, Late Spring follows themes that would come to define his work in the following decade — a daughter looking after her aging father, widowed patriarchs, and the loneliness of the human condition. Chishu Ryu plays an ageing widower who tries to convince his daughter to get married instead of staying to take care of him. The film, which is the first installment of Ozu’s Noriko Trilogy, involves a lot of prospective matchmaking and persuasion, and is a deeply felt, poignant piece of art that contains multitudes of character studies rendered with a loving eye.

3. Vengeance is Mine (1979)

Inspired by the true story of the serial killer Akira Nishiguchi, Vengeance is Mine recounts the story of how he committed the murders of over five people. The film portrays its main character in the light of a tragic, insane hero and also takes time to focus on his dysfunctional childhood, rendering audiences fascinated with the grisly and macabre crimes committed both in the fiction of the film as well as in real life. The film won the Best Picture Award at the 1979 Japanese Academy Awards.

2. Tokyo Story (1953)

Tokyo Story follows the Hirayamas, the husband Shukichi and the wife Tomi, as they visit their grown and married children, as well as Noriko, their widowed daughter-in-law. There is the unsaid sentiment present that as children grow older, they are more and more engrossed in their own lives and find it difficult to make time for their parents. The film neither condemns this fact, nor is fully comfortable with it, choosing to simply co-exist with the solitude of life like it’s characters do. Familiar Ozu themes of family, loss, and loneliness dominate the film.

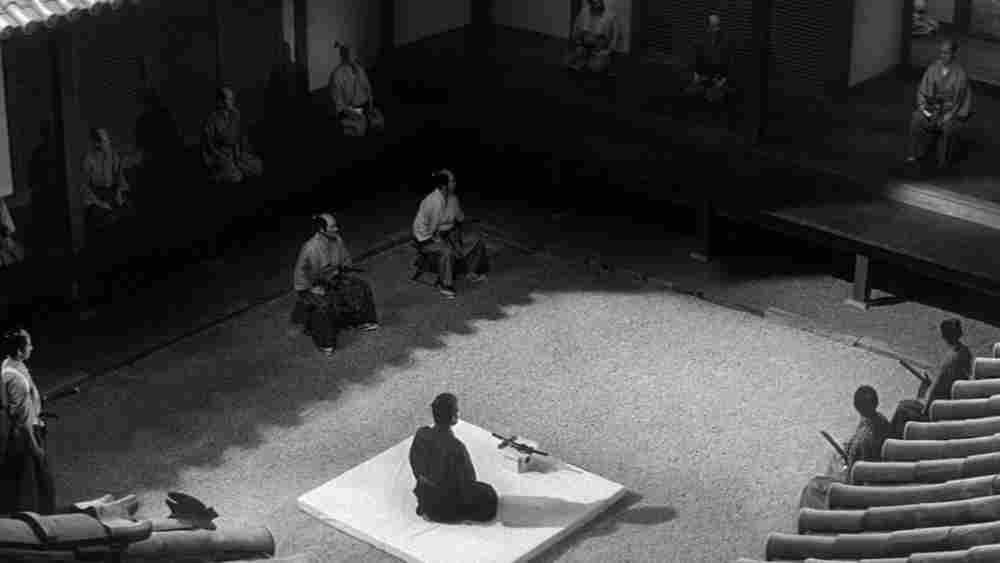

1. Seven Samurai (1954)

At the very top of our list (and many others) is Seven Samurai, an epic samurai film directed by Akira Kurosawa. The film features seven ronin who are hired by a village of farmers to fight off the bandits who plunder their crops. Honor, danger, epic fights and masterful swordplay — everything that makes a samurai film truly remarkable, this film has in spades, and some more. The film never quite mindlessly glorifies the heroic seven samurais of the title, or samurai code in general, instead choosing to take a morally grey approach and treating them like flawed human beings. The nuanced takes, sophisticated action and codes of conduct and hierarchy have made the film a cult classic both in its genre as well as the canon of Japanese cinema.

Conclusion

With great auteurs like Ozu, Kurosawa, Shimizu and Yoji Yamada, Japanese cinema is not just a fully formed, comprehensive body of work in its own right, but has also made great contributions to world cinema. Japanese classics continue to influence actors and filmmakers and its tonal approaches can be seen in the works of iconic modern-day filmmakers. With deeply human stories rooted in their vastly rich culture — spanning both the gritty cityscapes of civilized Japanese society as well as those that harken back to the idyllic countryside of old days — their stories cinema is profoundly cathartic and deeply rewarding.