The path one is meant to tread is drenched in mud—the kind that seeps up to your boots and pulls on your legs, trying to swallow you whole into an unforgiving, primordial abyss. A lone man walks forward, dragging an ominous coffin behind him; each step feels like a mile, the weight of the burden almost too much to bear. Still, he presses on. And then, through the haunting echo of an iconic score, we hear his name: Django. But this Django is not Tarantino’s liberated avenger. This Django hails from 1966, and he is no less iconic. Watch the film’s opening moments and you’ll understand why this character—and this film—commands a cult following. You may even find yourself drawn to its grim, magnetic spell.

Sergio Corbucci’s Django (1966) is among the finest Spaghetti Westerns never to feature Clint Eastwood. It celebrates and subverts the genre’s conventions while marking a breakthrough performance for Franco Nero. The film’s opening is almost biblical in tone—imbued with mystery, menace, and a strange, rugged grace.

Django does not shy away political undercurrents. The lingering wounds of the Civil War—specifically, the Union-Confederate divide—are never explicitly stated, yet their presence is palpable. Corbucci’s brilliance lies in implication, not exposition. The trauma of that national conflict ripples through every frame, shaping the lives of the characters in subtle, irreversible ways. This restraint spares the film from descending into didacticism, a trap that has marred many otherwise ambitious works.

We meet Maria, the female lead, as she is being whipped on a bridge by a Mexican gang. Rescued shortly after by the henchmen of Major Jackson, a sadistic ex-Confederate officer, Maria briefly seems safe—until the film reveals its true nature. Django is not a tale of rescue. It is a tale of brutal survival. Jackson’s men soon attempt to burn Maria on a cross. Enter Django, a drifter who storms in and dispatches the tormentors with a swagger Eastwood himself would be proud of.

The film’s central metaphor is powerfully laid bare, with the later ghost town episodes serving as natural extensions of that same bleak vision. This is no John Ford frontier; it’s harsher and more brutal. The violence—gritty, unapologetic—likely paved the way for Tarantino’s Django Unchained. The plot, if it exists at all, is threadbare. At times, the characters’ motives are unclear. But this is in no way a demerit to the movie. Life doesn’t always come with clean outlines. The story dangles by a shoelace, and that’s precisely the point. Corbucci takes the “Man with No Name” archetype and stretches it into something even bleaker. Franco Nero’s remote, emotionless performance has drawn its share of critique. But really, how much warmth survives in a world so ruthless? He looks exhausted, fractured—like a man eroded by the very soil he walks.

Django confidently blends genres. Gothic horror elements—ghost towns, gallows, and crucifixions—infuse the Western framework with an eerie melancholy. These tonal shifts are not jarring but seamless, revealing a filmmaker in full control of his craft.

The use of violence is particularly daring. In 1966, only low-budget exploitation films dared show such gore. But Corbucci’s violence is not sensational—it is unflinchingly real. And that realism dramatically ups the stakes, keeping us on edge throughout.

And yet, Django never feels gratuitously violent. It’s true to the era it portrays—a world where brutality was survival. Corbucci doesn’t sanitize his vision for broader appeal. He stays faithful to his theme: an America not yet civilized, but scarred and unresolved.

It’s no surprise Quentin Tarantino was so enthralled by this film. So were dozens of other directors, though few matched Corbucci’s audacity. Tarantino’s Django Unchained tips its hat to this legacy most memorably in a brief scene where Jamie Foxx meets Franco Nero. When Nero’s character asks Foxx’s Django for his name and receives the reply, Nero pauses and says, “I know.” A simple moment. A profound tribute.

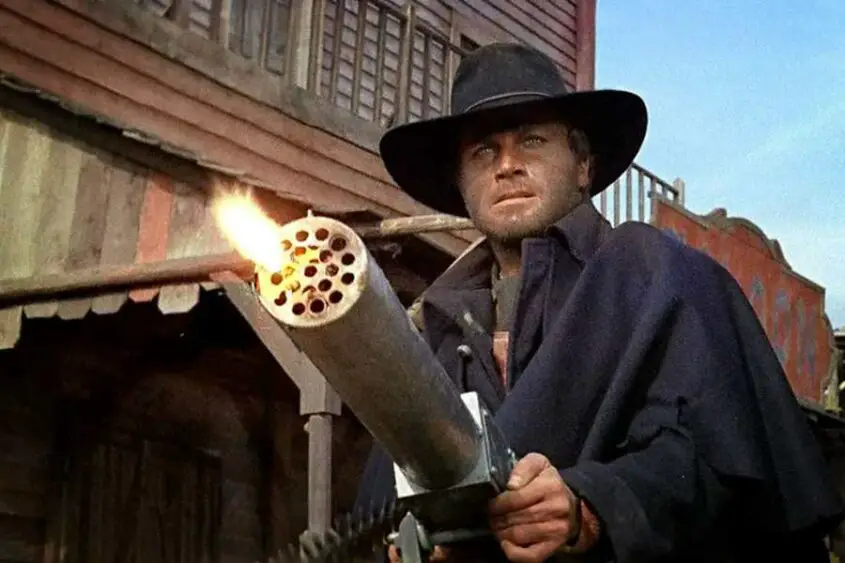

But Django is no story of redemption. In one of its most poetic ironies, our gunslinger has his hands smashed by horses. He’s unable to fire a gun, but still compelled to fight. A man made for violence, deprived of the very tool that defines him. It’s a tragedy masked as a Western and soaked in blood. And when the over-the-top Gatling gun fires, mowing down dozens, it doesn’t feel absurd—it feels inevitable. Because in Corbucci’s world, everyone is caught in the crossfire.

Much of the film’s legacy stems from the conditions in which it was created. Django was a risk. A shoestring-budget spaghetti Western shot in Italy, it operated with more grit than money. It was an indie in spirit, if not in distribution.

And yet, it spawned a wave of imitators—as many as 30 to 50 so-called “sequels,” many unrelated in plot but branded with the Django name by opportunistic distributors. The mythos grew not through loyal audiences but through unchecked replication.

Still, Django earns its pedestal. It’s not legendary because of marketing. It’s legendary because it changed the genre.

If you haven’t seen it, watch it. But don’t judge it by its trailer. It’s cheesy, chaotic, and wildly misleading. In those days, trailers were afterthoughts, not cinematic teases.

Overall, Django is essential viewing for any fan of the Western. It seamlessly weaves political commentary with operatic violence and atmospheric dread. With a 7.3 rating on IMDb and a well-earned 92% on Rotten Tomatoes, Django remains a compelling journey through a moral wasteland.

The pacing surprises—fluid where it should slog, jagged where it should settle. So give it time. Give it attention. Not the kind Predestination demands, perhaps, but focus nonetheless. Because if you blink, you’ll miss something important.

And finally, when you press play, remember what you’ve been told. The D is silent.

Rating: 3.5/5

Where to Watch: Prime Video

[Originally written by Deepjyoti Roy in 2019. This version was revised and updated by Mitch Farrell in July 2025]