The most enduring storytelling techniques in cinema didn’t emerge from nowhere—they’re translations of literary strategies that writers spent centuries developing. Drawing on French literary theorist Gérard Genette’s work on narrative structure and David Bordwell’s analysis of film form, this study traces how four fundamental techniques moved from page to screen: first-person narration, subjective point-of-view, non-linear time, and dialectical montage. Through close readings of films from Hollywood, Iran, and East Asia, I show how directors converted verbal devices into visual operations while solving the same narrative challenges—how to show what someone’s thinking, how to play with time, how to express abstract ideas through concrete images.

These strategies work across cultures and media because they’re built on cognitive fundamentals: how we actually process consciousness, memory, and meaning. They’re not arbitrary conventions—they’re aligned with how minds work. And the exchange runs both ways: contemporary novelists now write in ways deeply shaped by decades of cinema, proving this “common grammar” evolves through constant cross-pollination. I extend the analysis to prestige television and video games, showing how these principles adapt to new platforms while revealing where interactive media might finally break the pattern.

Introduction

Film theorists love to talk about cinema’s visual language—editing, camera movement, lighting, mise-en-scène—as if directors invented a whole new art form from scratch. But look closer at cinema’s narrative moves and you’ll find solutions to problems writers had already cracked: How do you get inside someone’s head? How do you fracture time without losing your audience? How do you make two unrelated images create a third idea that neither contains on its own?

Bordwell (Film Art: an Introduction) showed that filmmakers built on conventions inherited from novels and plays. Genette’s work on narrative gave us the precise vocabulary—focalization, temporal order, voice—to compare how stories work whether you’re reading them or watching them. I’m calling these continuities a “common grammar”: structural principles that hop between media, taking new forms in each but solving the same core problems.

Think about it: when a novelist writes “He remembered the war,” a director faces a puzzle. The solution might be a match cut from the character’s face to a battlefield decades earlier, or a sound bridge where artillery fire bleeds across time periods. These aren’t just adaptations—they’re visual-temporal equivalents addressing identical narrative challenges.

This study moves through four sections—voice, focalization, temporality, montage—examining how each literary technique became cinematic language. But I’m not limiting the analysis to Hollywood. Iranian and East Asian cinema offer crucial test cases: if this grammar is truly universal rather than just Western convention, it should work across cultural traditions. And finally, I look at the reverse flow—how cinema has reshaped how novelists write, proving this exchange runs in both directions.

The Confessional Voice: From Hardboiled Novels to Film Noir

Hardboiled detective fiction created a distinctive first-person voice: world-weary, ironic, confessing everything while trusting nothing. That voice doesn’t just describe events—it structures how we perceive them, filtering every detail through one damaged consciousness. Cinema grabbed this wholesale, using voiceover and framing devices to lock us inside a character’s subjective viewpoint.

Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity (1944) makes the technique literal: insurance man Walter Neff confesses into a dictaphone, his voiceover organizing the entire film as retrospective testimony from a doomed man. The voiceover doesn’t just narrate—it becomes the film’s moral architecture, his fatalistic tone coloring every sun-drenched Los Angeles street.

This strategy jumps cultures. Abbas Kiarostami’s Close-Up (1990) uses a similarly reflexive confessional structure, though in radically different form. The film documents real-life impostor Hossain Sabzian’s trial for pretending to be celebrated director Mohsen Makhmalbaf, but everyone involved—Sabzian, his victims, even Kiarostami himself—plays themselves reenacting events. Kiarostami positions us as judges, literally, through courtroom framing. We get Sabzian’s testimony but never full access to the truth. The technique works because the challenge is universal: how do you represent subjective reality, especially when the subject might be unreliable?

Paul Schrader’s essay on noir showed how voiceovers and flashbacks mark characters haunted by the past, unable to escape what’s already happened. But you don’t need voiceover to achieve this effect. John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon (1941) restricts everything to what Sam Spade sees and knows—we’re never ahead of him, never privileged with information he lacks. It creates the functional equivalent of first-person narration through pure visual grammar: composition, framing, what the camera reveals or withholds.

Noir’s visual style—harsh shadows, oblique angles, claustrophobic framing—works as syntactic markers externalizing interior psychological states, translating literary interiority into something cinema can actually show.

The Subjective Gaze: Stream of Consciousness Meets Camera

Genette gave us the term “focalization”—not who’s talking but who’s perceiving. It’s the crucial distinction for understanding how Woolf and Joyce’s stream-of-consciousness techniques have cinematic equivalents. Those modernist writers developed ways to render consciousness as associative flux, thoughts bleeding into memories bleeding into sensory impressions with no neat boundaries.

Cinema can’t give you verbal interior monologue as its primary tool, so it adapts: long takes that linger where attention lingers, point-of-view shots that literally put us behind someone’s eyes, depth-of-field manipulation that mirrors how focus shifts with attention, sound design that cues subjective awareness.

Here’s why focalization works across media: human consciousness operates through selective attention and associative jumps. Literary stream-of-consciousness and subjective camera both mimic how we actually experience reality—not as objective record but filtered through individual perspective. The technique persists because it addresses a fundamental challenge: representing what it feels like to be someone.

Antonioni’s L’Avventura (1960) lets camera movement and duration stand in for a character’s drifting, inattentive psychology. Nothing much “happens,” but the visual rhythm makes you feel disconnected awareness itself. Asghar Farhadi’s A Separation (2011) achieves something similar through strategic withholding: the opening positions us as the divorce court judge, but throughout the film no character—and therefore no viewer—gets complete information. We reconstruct truth from competing testimonies, which is exactly how consciousness works: limited, perspectival, prone to filling gaps with assumptions.

Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love (2000) uses slow motion, repetitive gestures, obstructed frames to create impressionistic focalization, prioritizing mood over clarity—the visual equivalent of remembering not what happened but how it felt.

Contemporary television extends focalization through seriality—think Succession‘s (2018) sustained intimacy with fundamentally opaque characters, or The Sopranos‘ (1999) dream sequences that break reality without breaking focalization. Interactive narratives push further: Disco Elysium (2019) gives you voiced internal dialogue from multiple aspects of your detective’s fractured psyche, while The Last of Us Part II (2020) forces you to inhabit radically opposed perspectives, creating enforced focalization impossible in passive media. You don’t just watch Ellie’s revenge quest—you control it, then control the person she’s hunting.

Unstuck in Time: When Chronology Becomes Optional

Genette’s work on temporal order gave us the vocabulary to discuss what Faulkner, Vonnegut, and Borges were doing when they shattered linear chronology. They discovered that disrupting sequence—jumping backwards (analepsis), forwards (prolepsis), or abandoning causality entirely—could generate meaning unavailable to straightforward storytelling.

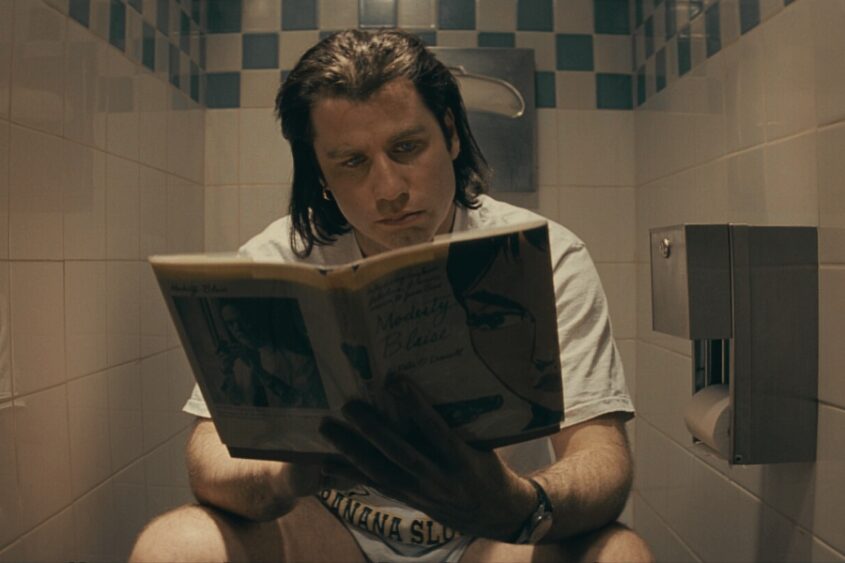

Cinema adopted these experiments wholesale. Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction (1994) arranges episodes out of chronological order not for gimmick but to create thematic resonances—you understand the diner scene differently having already seen what comes “after” it. Christopher Nolan’s Memento (2000) makes reverse chronology structural: experiencing the film mimics the protagonist’s amnesia, each scene erasing context the way his condition erases memory.

Why does non-linear narrative work? Because memory itself isn’t chronological. We don’t store experience as a linear sequence—we organize it thematically, emotionally, with salience determining what surfaces when. Both literary flashback and cinematic temporal disruption exploit how minds actually work, which explains why the technique translates across cultures. Denis Villeneuve’s Arrival (2016) makes this explicit: alien language restructures human temporal perception, and the film’s circular structure becomes inseparable from its thematic content.

The tools are different—montage rhythms, cross-cutting, parallel timelines—but they’re adapting verbal techniques of memory and prophecy into spatial-temporal sequencing that viewers actively reconstruct. The work of reconstruction is crucial. These films make you participate in building coherence, which creates investment that linear narrative can’t match.

The Syntax of Collision: Montage as Visual Grammar

Montage is cinema’s grammatical operation. Not just cutting from shot to shot but dialectical collision: A plus B equals something neither image contains alone. Kuleshov proved it experimentally—same shot of a face, different context shots, wildly different meanings generated in viewers’ minds. Eisenstein theorized it as conceptual synthesis, pure cinema achieving what individual images can’t.

The Odessa Steps sequence in Battleship Potemkin (1925) remains the textbook case: rapid cutting between soldiers, victims, the baby carriage creates emotional and political meaning that transcends any single shot. Hollywood absorbed dialectical montage into smoother continuity systems. Coppola’s baptism sequence in The Godfather (1972) intercuts religious ceremony with coordinated murders—the juxtaposition creates sustained irony about power and corruption, a visual syllogism.

But literature got there first. Dickens pioneered cross-cutting between parallel plotlines in his serialized novels, creating meaning through juxtaposition. Modernist poets used imagist techniques—placing discrete images together to generate conceptual sparks. Montage just formalized an existing literary strategy within the film’s temporal-visual syntax.

Reverse Influence: When Novelists Start Thinking Like Directors

The exchange runs both ways. Novelists who grew up watching films now write in ways shaped by decades of cinema, proving this grammar operates bidirectionally.

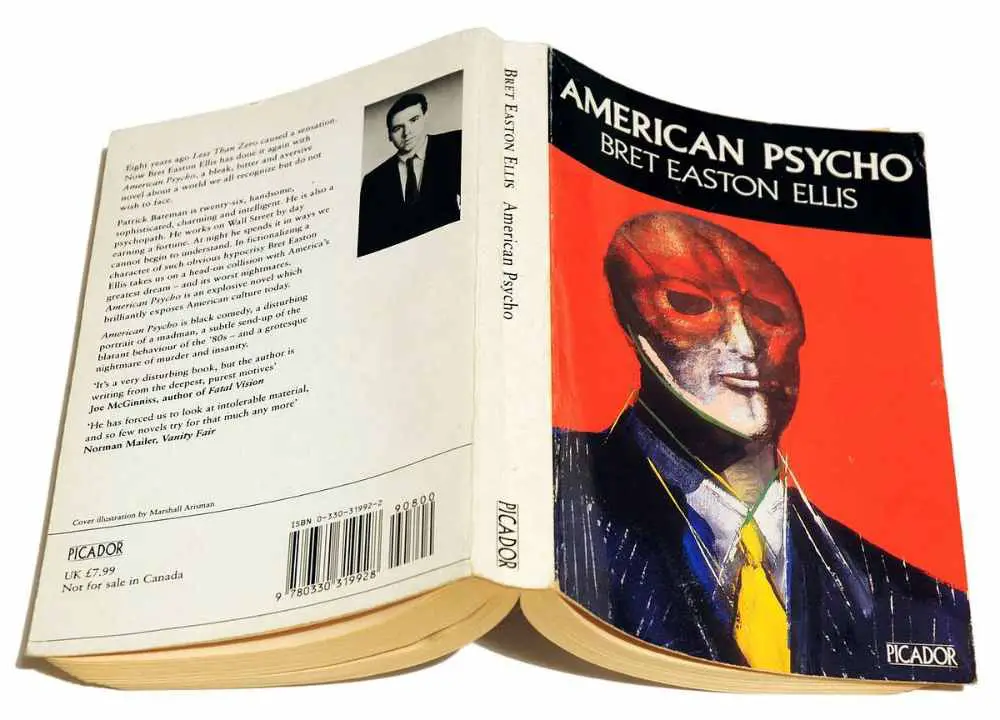

Bret Easton Ellis’ American Psycho (1991) reads like a screenplay in prose form: flat, affectless sentences cataloging brand names like camera pans across surfaces. Scenes cut abruptly without transition—literary jump cuts. The stream-of-consciousness mimics montage’s associative logic. Ellis admitted cinema shaped his detached style.

Cormac McCarthy’s later novels (The Road, No Country for Old Men) are nearly shooting scripts: minimal description, sparse punctuation, dialogue-driven scenes prioritizing visual action over interiority. It’s prose shaped by decades of watching films, particularly Westerns. Jennifer Egan’s 2010 novel A Visit from the Goon Squad includes a chapter formatted as PowerPoint slides—attempting multimedia, non-linear structure on the page.

This reverse influence confirms the grammar works bidirectionally. Narrative strategies migrate freely because they address cognitive storytelling challenges, not medium-specific constraints. Contemporary literature shows that cinema’s visual-temporal syntax has been reabsorbed into verbal narrative, completing a dialectical cycle.

Counterpoints: Where Media Resist Translation

Arguing for common grammar doesn’t mean ignoring what makes each medium distinct. Cinema’s visual affordances—simultaneity, framing, photographic indexicality—let it do things prose can’t match. Medium specificity theorists like Noël Carroll argue each art form has unique properties resisting translation: literature’s extended interior monologue, cinema’s indexical relationship to photographed reality, games’ procedural rhetoric through player choice.

Adaptation scholars push further, suggesting adaptations create fundamentally new works rather than translating existing ones. A film of a novel isn’t the book in different form—it’s a separate artwork with distinct interpretive possibilities. When directors convert literary first-person narration into voiceover, they don’t just transfer meaning—they create new affective registers specific to voice, performance, sound design.

Digital interactivity challenges the grammar’s limits most sharply. Can games have “unreliable narrators” when players control protagonists? Disco Elysium suggests yes—internal voices lie to the player-character—but player agency fundamentally alters focalization’s function. You’re not watching someone make choices; you’re making them, which changes everything about perspective and knowledge.

The grammar’s universality lies not in identical implementation but in addressing shared narrative problems across media and cultures. Cinema inherits functions from literature but rephrases them in visual-temporal idiom, creating new expressive possibilities. It’s a dialect, not a direct translation.

Conclusion

Tracing voice, focalization, temporal order, and montage shows cinema’s narrative syntax is deeply indebted to literary techniques even as it transforms them. This “common grammar” explains why certain strategies persist across media: they address how consciousness actually works—selective attention, temporal reordering, internal monologue, associative connection. These aren’t arbitrary conventions but cognitive fundamentals.

Testing the framework across Western, Iranian, and East Asian cinema demonstrates cross-cultural validity while acknowledging cultural inflections. The techniques translate because the challenges are universal, even if implementations vary.

The relationship between literature and cinema is dialectical: historical borrowing flows both ways, with contemporary novelists now writing in modes shaped by film. As narrative practices migrate into television and interactive media, the underlying grammatical principles persist, reconfigured by new technological possibilities. Contemporary literature’s absorption of cinematic techniques completes the cycle.

Future work might explore how emerging technologies—VR storytelling, AI-generated narratives, transmedia franchises—further test this grammar’s boundaries. But for now, the pattern is clear: certain narrative strategies work because they’re aligned with how minds construct meaning from experience. That’s why they travel so well.

Works/Films cited

Antonioni, Michelangelo, dir. 1960. L’Avventura. Cino Del Duca.

Bordwell, David. 1985. Narration in the Fiction Film. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Bordwell, David. 1993. The Cinema of Eisenstein. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Borges, Jorge Luis. Ficciones. Edited and introduced by Anthony Kerrigan, translated by Anthony Bonner et al., Grove Press, 1962.

Cain, James M. 1943. Double Indemnity. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Chandler, Raymond. 1939. The Big Sleep. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Coppola, Francis Ford, dir. 1972. The Godfather. Paramount Pictures.

Dickens, Charles. 1861. Great Expectations. London: Chapman & Hall.

Eisenstein, Sergei. 1949. Film Form: Essays in Film Theory. Edited by Jay Leyda. New York: Harcourt.

Faulkner, William. 1929. The Sound and the Fury. London: Jonathan Cape and Harrison Smith.

Genette, Gérard. 1980. Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method. Translated by Jane E. Lewin. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Gondry, Michel, dir. 2004. Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. Focus Features.

Hammett, Dashiell. 1930. The Maltese Falcon. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Huston, John, dir. 1941. The Maltese Falcon. Warner Bros.

Joyce, James. 1922. Ulysses. Paris: Sylvia Beach.

Juul, Jesper. 2005. Half-real: Video Games between Real Rules and Fictional Worlds. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Kuleshov, Lev. 1974. Kuleshov on Film. Translated by Ronald Levaco. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Malick, Terrence, dir. 1978. Days of Heaven. Paramount Pictures.

Mittell, Jason. 2015. Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Television. New York: NYU Press.

Naremore, James. 1998. More Than Night: Film Noir in Its Contexts. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Nolan, Christopher, dir. 2000. Memento. Newmarket Films.

Schrader, Paul. 1972. Notes on Film Noir. Film Comment 8 (1).

Tarantino, Quentin, dir. 1994. Pulp Fiction. Miramax.

Villeneuve, Denis, dir. 2016. Arrival. Paramount Pictures.

Vonnegut, Kurt. 1969. Slaughterhouse-Five. New York: Delacorte Press.

Wilder, Billy, dir. 1944. Double Indemnity. Paramount Pictures.

Woolf, Virginia. 1925. Mrs. Dalloway. London: Hogarth Press.

Disclaimer: Some of the above are affiliate links. We may earn a commission if you make a purchase.