Whether novelist R.K. Narayan was happy or upset after watching ‘Guide’ is of little consequence because the romantic drama, directed by Vijay Anand, was declared a super hit at the marquee. Besides, it won critical international acclaim and was India’s official entry for the Oscars in 1966. The runaway success of this literary adaptation should have inspired mainstream Hindi filmmakers to try out Indian English novels as worthwhile subjects for cinematic forays and spark a new trend. But the fact is that there were very few Indian authors of considerable merit during those days.

The triumvirate of R.K. Narayan, Raja Rao and Mulk Raj Anand dominated the literary scene although the emergence of new writers such as Khushwant Singh with ‘Train To Pakistan’ and Ruskin Bond with ‘The Room on the Roof’ was changing the English literary landscape in India.

Perhaps enthused by the success of ‘Guide’, Vijay Anand mounted his next film ‘Tere Mere Sapne‘, starring Dev Anand and Mumtaz, based on an English novel, ‘The Citadel’, authored by a Scottish novelist AJ Cronin, and published in the UK. The lukewarm response at the box-office was a dampener when it was released in 1971. The tryst with literature was a short-lived affair as there weren’t too many Indian novels in English with cinematic potential during those days, hence the scope of finding suitable ones was indeed limited.

Books And Parallel Cinema

While regional Indian literature comprising short stories and novels was finding acceptance in Hindi cinema, thanks to visionary directors like Bimal Roy, Gulzar and Basu Chatterjee who continued to scout for regional stories, Indian English novels had to wait a long while for the birth of parallel cinema to find new takers. Ruskin Bond’s novella ‘A Flight of Pigeons’ was made into a film by Shyam Benegal in 1978. Despite Shashi Kapoor and Shabana Azmi playing key roles, it was not listed as a mainstream Hindi film.

However, Ruskin Bond and his storytelling did interest other filmmakers later – like auteur Vishal Bhardwaj who made several films – ‘Haider’, ‘Omkara’, and ‘Maqbool’ – on Shakespearean sources. Ruskin Bond’s novella ‘The Blue Umbrella’ inspired Vishal Bhardwaj to make a film on the same title in 2005. Another Ruskin Bond short story, ‘Susanna’s Seven Husbands’ was the base for Bhardwaj’s ‘Saat Khoon Maaf’ starring Priyanka Chopra in 2011.

Indian films based on Indian English novels were made in English for the global audiences and the international film festival circuit. Thus began a period of resurgence with independent movies like Dev Benegal’s ‘English August’ that won the National award for the Best Feature Film in 1994. While many foreign English novels and short stories considered classics were made into Hindi films like ‘Sawaariya’ and ‘Lootera’ and many literary works of Sarat Chandra and Premchand were made into successful films, there was a lean phase when Indian novels in English were considered fit for English films made in India and the offbeat directors were left with the job of handling them for multiplex audiences.

Literature’s Tryst With Mainstream

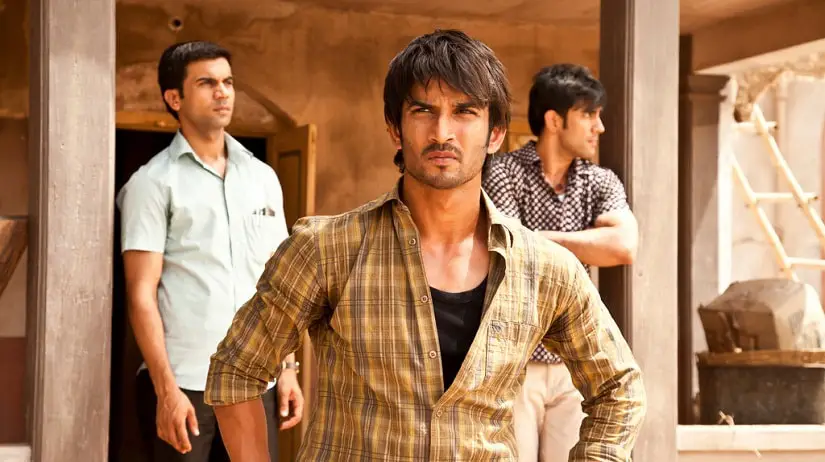

What changed the game was the arrival of Chetan Bhagat on the literary scene whose 2004 cult book, ‘Five-Point Someone’ was made into coming-of-age comedy-drama ‘3 Idiots’. It was a trailblazing success and became the highest box office grosser in 2009. The blockbuster film made Bhagat a favourite novelist in Bollywood and soon after his novel, ‘One Night At The Call Centre’ was picked up for ‘Hello’ that generated average business. ‘Kai Po Che’ in 2013 brought his next novel, ‘Three Mistakes Of My Life’ on the Hindi screen and the film did quite well at the box office. In 2014, ‘Two States’ directed by Abhisek Varman was released successfully.

For more than a decade now, it has become a norm to convert Bhagat novels into films and he is the only author with almost all his novels being made into films. Much to the chagrin, his ‘Half Girlfriend’ in 2017 didn’t make producers happy. Bhagat joining Bollywood as a screenwriter hasn’t given any Kick to his career. One can hope that his recent novels also get adapted and accepted by viewers. With his new novels trying out other genres without repeating his previous successes, it’s safe not to pitch expectations too high.

Acceptance Of Indian Novels

Leave aside the biopic category and the works of non-fiction from the realm of consideration and let’s look at Indian English novels and the authors of Indian origin writing in English. Anita Desai’s Booker Prize-shortlisted ‘In Custody’ deserves a special mention here. It was adapted to Hindi film by the legendary producer-director, Ismail Merchant. Based on the life story of poet Nur played convincingly by Shashi Kapoor and Om Puri essaying the role of the professor struggling to conduct the interview despite multiple glitches. It’s not a film to be included in the mainstream Hindi cinema, just like ‘The Namesake’ based on Jhumpa Lahiri’s novel cannot be classified completely Indian as it was made by Mira Nair for the international audiences.

Now, with Indian English writing coming into a robust form, there are good Indian films based on them. Arvind Adiga’s Booker-winning novel ‘The White Tiger’ mixes Hindi and English. It is directed by internationally acclaimed director Rahim Bahrani, the man behind ‘Man Push Cart’. Whereas ‘Serious Men’ is an Indian Hindi-language satirical comedy-drama directed by Sudhir Mishra. The film, featuring Nawazuddin Siddiqui in the lead role, is based on the book by the same name written by journalist-author Manu Joseph.

As Sudhir Mishra straddles both the art and the middle cinema world with élan, his film can be counted as a worthy example of how Indian English novels are now getting accepted. With web series coming in a big way and the scope widening further with Netflix and other streaming platforms, there is a spurt in demand for fresh content of a different kind. Filmmakers keep track of crime fiction, literary fiction, social dramas, and love stories hitting the bookshelves, to hunt for cinematic potential in the new arrivals. It’s a fact that not every successful book has cinematic possibilities and visionary filmmakers can detect that easily.

Literature With Cinematic Potential

‘The Black Prince’ directed by Kavi Raz was made in 2017 on the life of Maharaja Duleep Singh, but it suffered because of a weak script. But biographical period dramas hold immense cinematic potential for the Indian audiences. For instance, ‘The Last Queen’ – if made into a film – will have a different fate at the box office. Like all her previous novels, Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s latest best-selling novel is a historical retelling of the life of Maharani Jind Kaur. It bears immense potential in terms of narrative strength.

Like Rani Lakshmi Bai and Padmavati, Jindan Kaur, Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s youngest and last queen, became a warrior queen to protect her son’s heritage and fought bravely to prevent the British from annexing Punjab. A story of love between a king and a commoner, loyalty and betrayal, the novel depicts an intrepid lady of the 19th century who still inspires women of this generation.

Rupa Bajwa’s ‘The Sari Shop’, an award-winning novel published in 2004, has a simple yet engaging storyline. It deals with issues of class feminism and hypocrisy, depicting a contemporary world of hope and violence through Ramchand who works in a sari shop and learns English. It is a right fit for the kind of offbeat films being made in Hindi these days.

Sujit Saraf’s ‘The Confession of Sultana Daku’ was in discussion to get adapted into a feature film starring Nawazuddin Siddiqui. His latest acclaimed novel, ‘Harilal and Sons’ also has a powerful storyline mapping the journey of a 12-year old Marwari boy from Rajasthan to Kolkata — a saga that should appeal to lovers of quality Hindi cinema.

Conclusion

There is no dearth of good novels in Indian English fiction today. Filmmakers seeking literary sources now realise they have a fantastic opportunity to trust authors instead of depending on scriptwriters with original ideas and storylines that haven’t been tested in the market. Watching hundreds of foreign films and then rewriting them with tweaks here and there is not going to create an impact on audiences with a voracious appetite for home-grown content, stories that are coming from their lives and of those around them. The English language now is as much a part of the Indian culture and hardly a stumbling block in terms of adaptation if the story makes the cut.