What if the most breathtaking moment in cinema wasn’t about saving the world — but about defying the impossible?

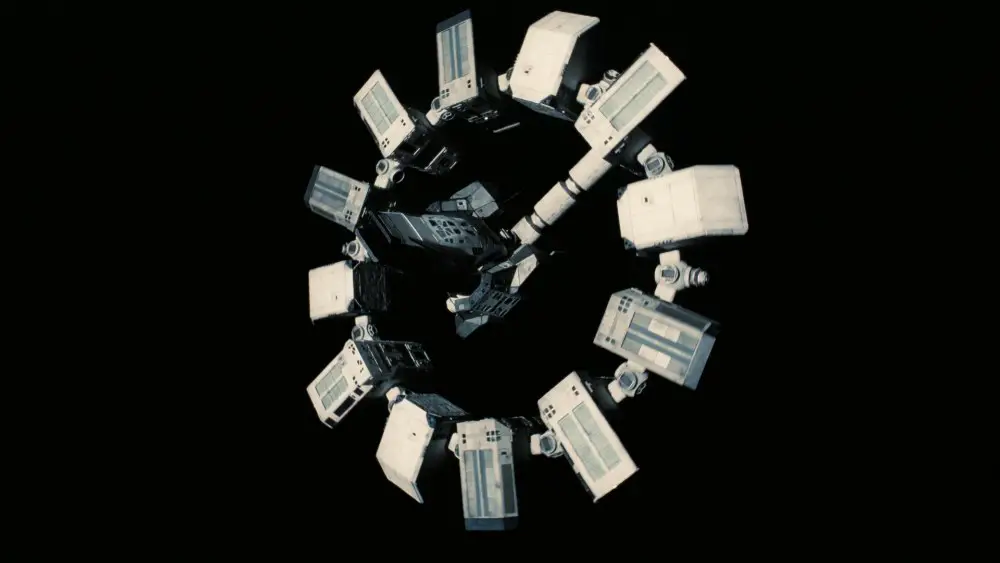

The docking scene in Interstellar distills everything Nolan does best — precision, tension, and chaos in perfect sync. Cooper fights physics and fate all at once.

But beneath all the spectacle is a story about love, time, and the terrifying beauty of not knowing our place in the cosmos.

INTERSTELLAR EXPLAINED

Where It All Began

The story begins with Cooper, a former NASA pilot turned farmer, grappling with a dying Earth. Dust storms rage, crops fail, and hope is fading.

There’s no flashy apocalypse imagery — just a quiet collapse of civilization that’s stopped looking up.

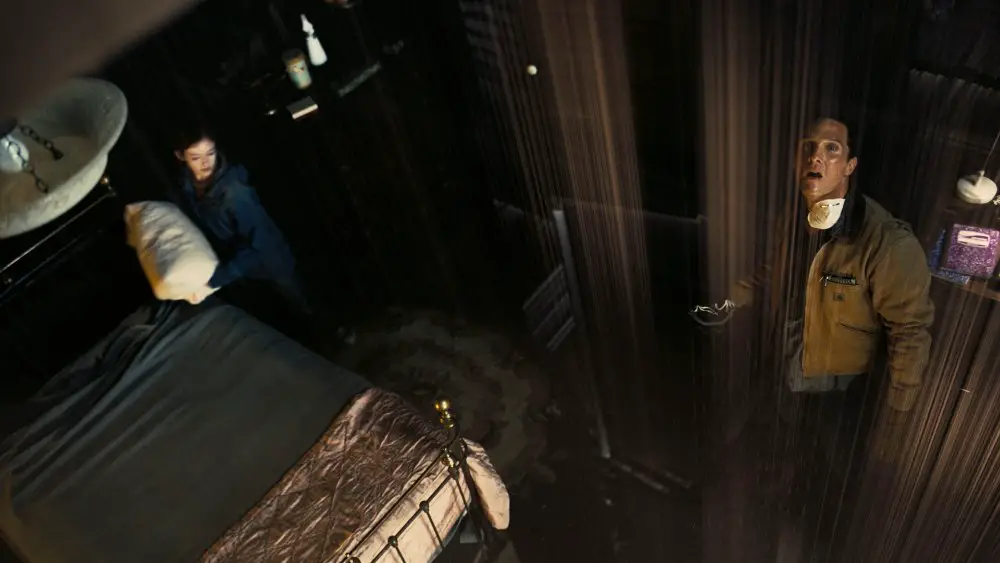

Cooper’s daughter, Murph, believes there’s a “ghost” in her room — something moving objects, leaving strange patterns in the dust. But it isn’t haunting; it’s gravity, trying to communicate. The anomaly leads them to a set of coordinates — a hidden NASA facility long thought defunct.

Inside, Professor Brand and his team are planning one last mission to save humanity.

And Cooper becomes their best pilot — but the cost is devastating: he has to leave his children behind — maybe forever.

The coordinates, the anomaly, the timing — nothing feels random. It’s as if something, or someone — is guiding them.

Beneath all the science, the film never loses sight of what drives its characters. Connection.

Cooper’s bond with Murph gives the mission its heart. There’s a reason for him to return to Earth, but there’s more to it than that.

Before leaving, Cooper gives Murph his watch. That watch isn’t just a keepsake.

When Time Becomes The Enemy

Time is of essence in Interstellar.

Reaching the wormhole near Saturn is a two-year journey alone. Aboard the Endurance, Cooper’s crew — Amelia Brand, Romilly, Doyle, and the robots TARS and CASE — set out on a mission that could save humanity or strand them forever.

Their task: explore three potentially habitable planets identified through the wormhole — Miller, Mann, and Edmunds, named after the scientists who first surveyed them. All three orbit a massive black hole called Gargantua.

The first planet, Miller’s, is an endless ocean where one hour equals seven years on Earth. Miller’s already gone, wiped out by the tidal waves. It’s a brutal reminder of how quickly time can destroy everything we fight to preserve.

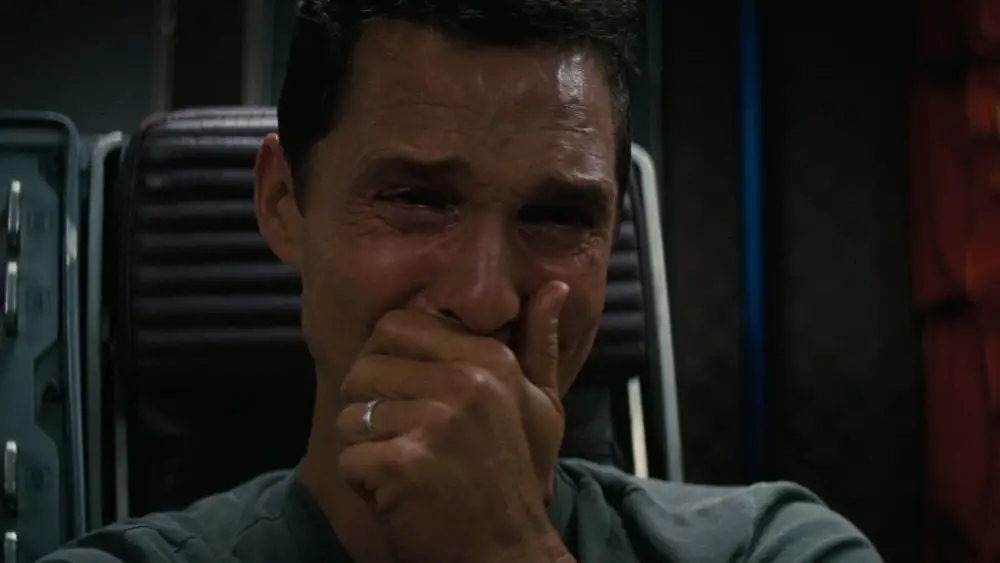

After losing Doyle and barely escaping, Cooper and Brand return to the Endurance — only to find that 23 years have passed on Earth. Murph is now grown, and Cooper watches decades of her life unfold in minutes. It’s one of the film’s most devastating moments.

Love is the Key

In one of the film’s most debated scenes, Dr. Brand says:

“Love is the one thing we’re capable of perceiving that transcends dimensions of time and space.”

That line might sound corny but it’s an unmistakable theme of the film. Love, not logic, drives the mission.

It’s what keeps Cooper going — the need to make sure Murph has a future.

Brand, meanwhile, still hopes to reach Edmund, the man she loves, stranded on another planet.

But getting there would take more fuel, meaning Cooper could never return home.

Love inspires — but it also clouds judgment. Cooper calls Brand out for letting emotion override reason. Eventually, they head to Mann’s planet — its signals are stronger, and it’s closer.

But what’s riskier than love clouding judgment? Desperation.

Mann’s planet is a frozen wasteland. When the crew lands on his planet, they find Mann’s alive, but broken. His data was fake. He lied only to be rescued.

His deception costs Romilly his life and almost kills Cooper. Mann’s recklessness ends in his own death when he fails to dock safely with the Endurance.

His death is a lesson: Survival alone isn’t enough. Without purpose, it’s meaningless.

With the Endurance running low on fuel, Cooper and Brand make one final gamble — use Gargantua’s gravity for a slingshot to send Brand toward Edmund’s planet.

The plan: drop TARS into the black hole so it can gather data from inside the singularity — data that might finally save humanity.

What’s Singularity?

It’s the center of a black hole — where gravity’s so strong time, space, and physics stop working the way we know them. Anything that gets too close, is crushed. Yet, paradoxically, it’s also a place of creation.

TARS dives in first to gather quantum data from near the singularity before it’s destroyed. Cooper follows, detaching his module to give Brand enough momentum to reach Edmund’s planet — a sacrifice that also puts him in position to reach that data.

He awakens inside a mysterious Tesseract — a vast, multi-dimensional lattice of Murph’s childhood bedroom. Time isn’t linear here. It exists all at once. It’s physical, tactile. Cooper can move through it, reach into moments, communicate across the past.

Why Murph’s Room?

Because it’s the one place Cooper can reach Murph — the point where gravity already connected them across time.

It’s where the anomaly first appeared, where Murph noticed the “ghost.” The tesseract was built around that moment so Cooper could send the quantum data she needed to solve the gravity equation — humanity’s only way off Earth.

Inside, he realizes he was the ghost all along. Using gravity, he encodes the data into the watch’s second hand, giving Murph the key to complete the equation and save humanity.

For years, Professor Brand claimed to be close, but the missing piece — the quantum data — could only come from inside the black hole, from the singularity itself.

If Cooper hadn’t found it, humanity’s only fallback was Plan B: seeding life from embryos on another world — a plan he never knew existed when he left.

Ending Explained: Who Built the Tesseract?

Cooper realizes the tesseract was built by future humans — referred to as “they” in the film.

How they created it doesn’t matter. What matters is why they did: to give humanity a way to survive.

Just as Cooper was able to guide Murph with his love, someone, somewhere, wanted him to succeed as well. Love eventually serves as an explanation for the tesseract itself. It’s a time loop of compassion, not paradox.

Murph decodes the watch and solves the gravity equation. Humanity escapes Earth.

Cooper survives, rescued by people aboard a massive space station named after his daughter.

He reunites with Murph, who’s aged eight decades and now near death, while Cooper’s barely aged, thanks to time dilation.

“No parent should have to watch their child die,” she tells him. (keep video clip as is)

Edmund didn’t survive, but Brand has landed safely on the new planet.

The ending isn’t just about survival — it’s about creation. Inside the black hole, the singularity becomes both an end and a beginning, where destruction gives birth to understanding. Future humans built the Tesseract to help Cooper send Murph the data — closing the loop that began with the “ghost” in her room. The singularity becomes the point where science and love intersect.

The Science Behind Interstellar

Interstellar draws from several sci-fi classics — 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Right Stuff, Solaris, Silent Running, and Apollo 13. But it comes closest to Robert Zemeckis’s Contact from 1997, which was based on Carl Sagan’s novel. In the film, Jodie Foster plays a scientist decoding a message from deep space — a blueprint for a machine that lets her travel across the universe and, ultimately, confront something deeply personal: the loss of her father.

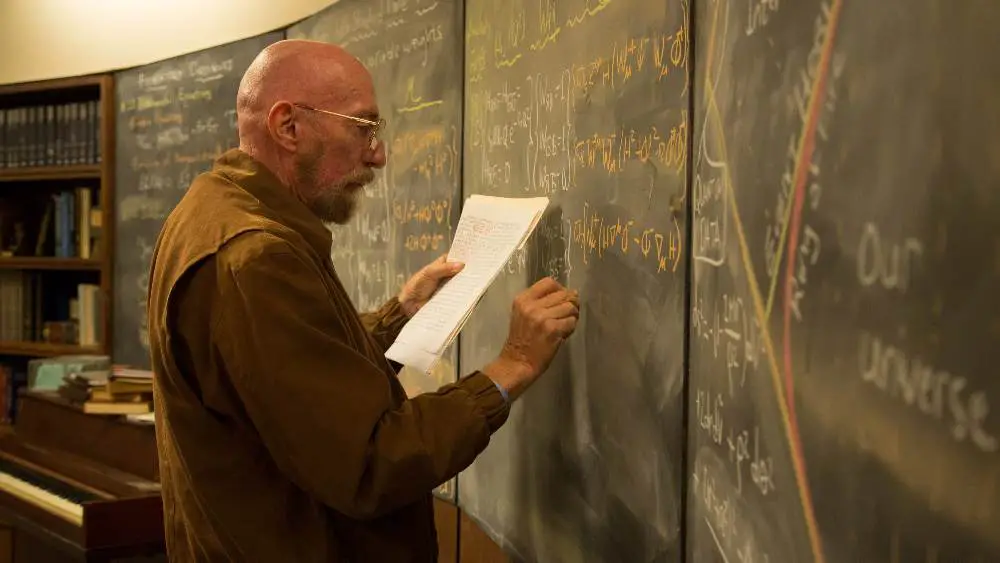

If that sounds familiar, it’s no coincidence. Sagan’s novel was inspired by physicist Kip Thorne’s research on wormholes — the same science that would later shape Interstellar. Thorne and producer Lynda Obst, who’d also worked together on Contact, began developing their own space story — an idea that eventually became Interstellar, with Steven Spielberg originally attached to direct.

The project truly took shape when Jonathan Nolan came on board to write the script — originally for Spielberg’s version. He spent years studying relativity, NASA’s real challenges, and even the Dust Bowl of the 1930s to ground the story’s dying Earth in reality. When Spielberg left the project, Christopher Nolan stepped in, refining his brother’s script into the film we know today.

For the film, Kip Thorne helped design the black hole, the time-dilation effects, and the tesseract sequences. And if you’ve ever wondered how any of it could actually work — from bending space-time to sending data through a watch — Thorne breaks it all down in his book The Science of Interstellar.

Nolan took creative liberties, sure, but Interstellar still gives us one of the most realistic black holes ever shown on screen — real enough that even scientists argued over it.

And beneath all that science and spectacle, Interstellar to me, is really about one question — what does it mean to stay human when everything else fades? Something to think about the next time you marvel at that docking sequence.