Mise-en-scène, a phrase from the French language pronounced meez-on-senn, originated in the theater somewhere in the early 19th century. So, what is a mise-en-scène? In English, it simply means ‘staging’, i.e., arrangement of actors, scenery, and props in a theatrical production. In relation to cinema, the term was first popularized by renowned French film theorist and critic André Bazin. Bazin calls mise-en-scène, “an important aesthetic revolution that choreographed movement within the scene rather than through editing.” Therefore, in film analysis, the term denotes the contents of the frame: lighting, production design, performers, composition, and costumes.

The Oxford Dictionary of Film Studies mentions that mise-en-scène can also refer more broadly to the relationship between onscreen and off-screen space created by the framing of the image and the camera movement. Sounds too complex?

Take this unnverving, confrontation scene in Kubrick’s classic The Shining. The action takes place in a staircase. Wendy is horrified after discovering her husband Jack’s manuscript. Jack, on the verge of madness, ascends the stairs as a frightened Wendy, clutching a baseball bat, slowly retreats. Apart from the astounding performance by the two actors, the precision with which Kubrick composes each frame within this fluid scene to elicit great tension was nothing short of phenomenal. The scene is the culmination of all the dramatic tension built in the narrative. Hence, a close-reading of the mise-en-scène here is essential to comprehend Kubrick’s use of space, actors, and the emotions.

Why is mise-en-scène important?

For now, let’s understand mise-en-scène as the ubiquitous element that guides a viewer’s attention and produces meaning. When all the components of mise-en-scène work perfectly, a series of moving images hold the power to move you. So, to understand the purpose and significance of a mise-en-scène, let’s take a look at these elements and their relevance in a film.

Elements of a mise-en-scène

Composition

Bunch of scenes make a film and a bunch of shots make a scene. A shot is a single, distinct unit that comprises of frame(s) that run for an uninterrupted period of time. To design a shot, a filmmaker has to consciously choose the frame and camera angles that will accentuate his visual expression. Therefore, composition is choosing the ingredients that make up a shot. A perfect shot can communicate a lot – from precise emotions to themes – to the audience.

Composition offers infinite potential and flexibility for the filmmakers. The other crucial part of composition is ‘blocking’, i.e., movements displayed within a shot in relation to the camera. Both composition and blocking are intricately connected with the other components that follow.

Production Design

Production or set design refers to the overall visual look of the frame or a film as it appears on the screen. A production designer primarily needs to create a consistently convincing reality within which a fictional world is set. Take for instance, a film set in the 1970s and a frame that shows the character’s living room. The production designer needs to find, adapt, and place things that match the period.

Production design is essential to create a fitting atmosphere for the narrative. It’s a job that requires a basic understanding of all technical aspects of filmmaking. Art direction comes under production design. While production design sets the entire look of the film, the skills of an art director are required to implement each creative design. In large-budget films, an art director works under a production designer, alongside the departments of action, special effects, and so on. Naturally, the choices made by the production designer simultaneously influence the costumes, hair and makeup departments.

Film Texture

Texture in film is also closely associated with the final look of a movie. From the type of camera one chooses to the complex set of filters employed in post-production, deciding on film texture is also vital to immerse a viewer into its fictional world. Choosing a particular texture requires the collaborative effort of the director, cinematographer, and production designer. Apart from opting for a fine or grainy look, usage of color is part of texture. As Patti Bellantoni writes in the book If It’s Purple, Someone’s Gonna Die: “Our feelings of euphoria or rage, calm or agitation can be intensified or subdued by the colors in our environment. This is powerful information in the hands of a filmmaker.”

Lighting

The third most vital component of mise-en-scène is lighting. Nothing conveys a mood within a frame as precisely as a good lighting technique. High-key lighting denotes a brilliantly lit scene with minimal shadow and dominant source of illumination. This is primarily used in Hollywood musicals among many others. Low-key lighting features a high-contrast lighting pattern, i.e., a considerable contrast between bright light and shadow. This type of lighting is usually seen in horror movies. There are also many types of specialized lighting which play a significant role in creating dramatic effects.

Costume Design

Costume design is a relatively new area among film studies although clothing and props worn by actors have long been a crucial element of mise-en-scène. A film’s subject matter as well as a filmmaker’s vision leads to the choices surrounding costume. For instance, in classic Hollywood, costumes played a pivotal role in constructing the star persona. In classic gangster films, the life of excess and spectacle was achieved through the use of costumes. Since costumes are signifiers of one’s status, power, and identity, it is essential to shape a character’s look.

Hair and Makeup

Makeup can enhance or transform an actor’s appearance to fit into a character. In mainstream cinema all over the world, hair and makeup is necessary for beautification aspects. But in general, makeup provides visual consistency to the characters on-screen. It can conceal as well as highlight the blemishes a filmmaker wants you to see in a character. Makeup and costumes play an important role in historical cinema. Makeup, however, set astounding benchmarks in horror cinema. On-screen gore and blood, monstrous creatures that gave us nightmares were the result of transformative makeup.

Whether we realize it or not, all these key elements of mise-en-scène come together to make a cinema or a scene unforgettable.

Let’s take a look at a few examples where the mise-en-scène pulled us deeper into the fictional realm:

Mise-en-scène examples in Films

1. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920)

Like I said, the notion of mise-en-scène was created by the film critics of France. André Bazin and other contributors to Cahiers du Cinéma — a French film magazine founded by Bazin and Jacques Doniol-Valcroze, Joseph-Marie Lo Duca — brought up the term. The method, however, already existed in some manner. Particularly from the mid-1910s when cinema gradually evolved into an art form. The German Expressionist film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari was known for its smart use of mise-en-scène.

The sets, lighting, and cinematography came together to create a deranged, nightmarish world. To design the eerie atmosphere in Caligari, director Wiene and his designers Reiman and Rohrig filled the set with flat light and then painted the shadows directly onto the floors and walls. Therefore, this was one of earlier films to narrate a story through its perfectly made-up environment.

2. Citizen Kane (1941)

Orson Welles and cinematographer Gregg Toland pushed the possibilities of deep staging action and characters in Citizen Kane canonizing its visual style. Jean Renoir and John Ford in Stagecoach have employed deep focus and deep space. But it was so dynamically and outstandingly utilized in Citizen Kane. Deep focus is a technique where all the elements of an image – foreground, middle ground and background – remain in sharp focus. In Citizen Kane – a powerful story of a newspaper magnate – Welles did an unbelievable amount of spatial experiments. Filmmaker and critic Mark Cousins notes that this film “extended the dimension of the screen to its limits.”

3. Tokyo Story (1953)

While Hollywood was involved in extending the parameters of mise-en-scène, there were also the great minimalists: Ozu and Bresson. Ozu’s mise-en-scène is very distinct from among the global filmmakers. Not just the characters’ position in a space, but the space itself is treated uniquely in Ozu’s cinema. Ozu’s domestic dramas conveyed deeper philosophical ideas about family, individuality, change, and death. The space or surface in Ozu’s cinema is mundane. But it withholds deeper questions about human existence.

To understand how the simple aesthetics of everyday life is turned into a visual poem, one can start with Tokyo Story. Its plot is simple: elderly parents visiting their grown-up children in the city. However, its impeccable mise-en-scène hauntingly conveys the beauty, loss and suffering inherent in life.

WATCH: 10 Greatest Yasujiro Ozu Films, Ranked

4. Pickpocket (1959)

Pickpocket revolves around the experiences of a petty criminal named Michel. Robert Bresson, in his previous film Diary of a Country Priest, utilised his character’s journal entries to get deeper into his psyche. In Pickpocket, Bresson’s mise-en-scène emphasizes more on the simplicity. It rejects almost all visually and emotionally stimulating frames or what Bresson considers superficial. What the director suggests through his scaled-down mise-en-scène is the spiritual imprisonment of the individual. Hence, the austerity and tight framing becomes his natural formal choice to highlight the thematic preoccupations.

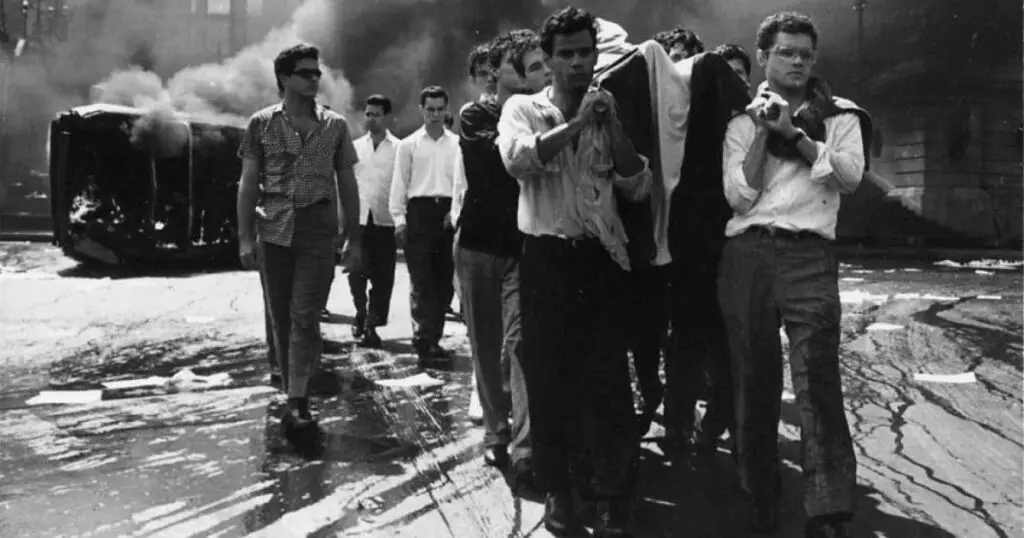

5. I Am Cuba (1964)

The early Soviet Russian movies offered unique editing styles to the world of cinema. But there were quite a few Russian filmmakers who manufactured visual spectacles like their Hollywood counterparts. Mikhail Kalatazov is one such important Soviet filmmaker whose idiosyncratic mise-en-scène is absolutely breathtaking for its time. Critically panned during its release, I Am Cuba was long-forgotten until the American filmmakers Scorsese and Coppola brought it to cinephiles’ attention. I Am Cuba is a pro-Castro agitprop film that’s episodic in nature. From the acrobatic movements in the opening scene to the remarkable funeral procession scene, it’s a perfect example of creating an epic mise-en-scène tableau.

6. Titanic (1997)

In the more recent times, James Cameron’s epic romance and disaster film is largely memorable for its bewitching use of key mise-en-scène elements. The biggest challenge is that it’s wholly set in a ship sailing in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. Moreover, deep space is often used where even the far view of the ship is in clear focus. The use of lighting and costumes conveys the difference in classes within the ship. In the later half of the film, particularly, low-key lighting is used to express the epic tragedy. It wasn’t the tragic love story alone that made Titanic the success it was. The awe-inspiring visuals played an equal role. Now, that’s the power of a meticulously-designed mise-en-scène.

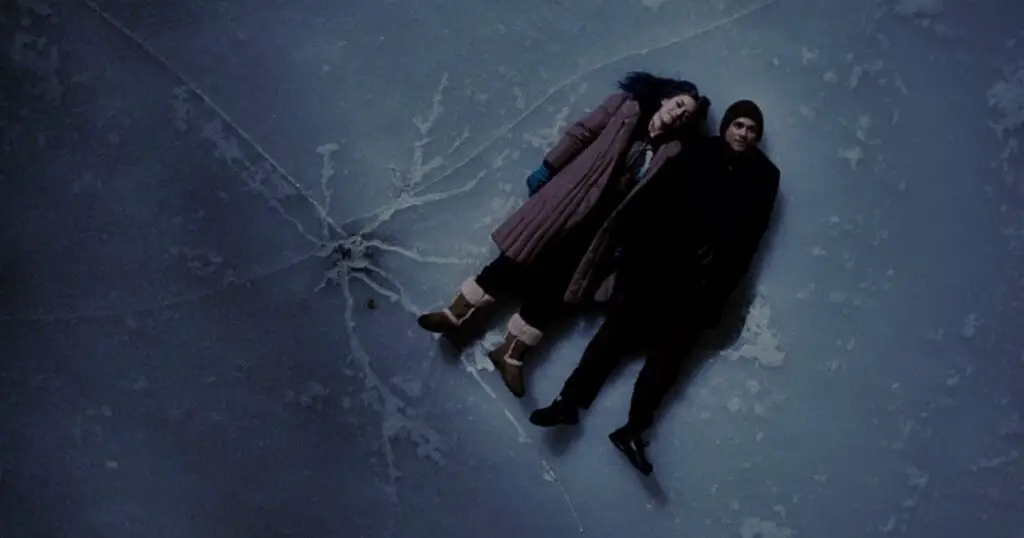

7. Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004)

Michel Gondry’s popular romantic film chronicles the pleasure and agony of love. It contemplates on the nature of memory and our innate desire to avoid suffering. A surrealist element is introduced into the narrative. The protagonist, to avoid the pain of his break-up, opts to erase the memories of his ex-girlfriend. While the uncanny use of mise-en-scène is apparent right from the opening scene, the exploration of the memory world is truly astounding. The lighting and use of color play a vital role in conveying the mood throughout. Even the costumes the characters wear provide significant visual cues. The film’s inventive mise-en-scène lends emotional heft and resonance to the story.