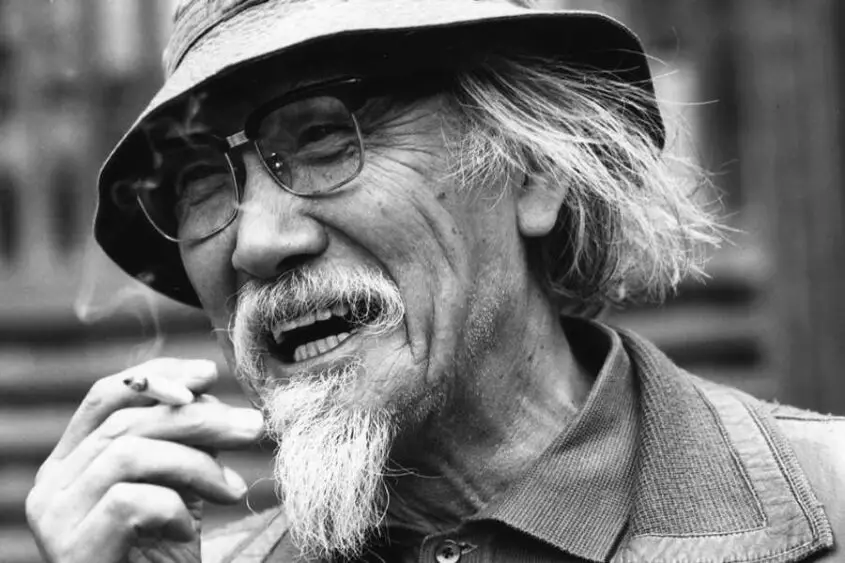

He made a movie so strange, his own studio fired him. He was blacklisted for a decade. This isn’t just the story of a film. It’s the story of a man who refused to be ordinary — even when it cost him everything. He was an outsider. A rebel. And one of the most visually daring directors Japan has ever seen. That odd man was Seijun Suzuki.

This was a guy with films as wild as his hair. But he didn’t start that way. There was a time when Suzuki was more of a B-movie director. Those were his early days at the Nikkatsu studio. For a studio aiming to crank out many pictures, Suzuki was ideal. He’d be assigned a script and run with it.

If Nikkatsu wanted a B-movie only meant to showcase pop music, Suzuki was their guy. In fact, that was the case with his official directorial debut — 1958’s Victory is Mine. The studio was so impressed by this movie they signed him on for more. Suzuki became their filmmaking machine. He could turn in commercial films on time and on budget.

At Nikkatsu, Suzuki was making an average of 3 movies a year. But his most prominent genre? YAKUZA. Japanese gangster films were in high demand in the 60s. Having proved his worth with 1958’s Underworld Beauty, Suzuki’s talents in this genre grew further.

From B-Movies to Best Movies

He really hit his stride with 1963’s Youth of the Beast. This wasn’t a typical yakuza film. It wasn’t even a typical Suzuki film. The man was used to just replicating whatever the studio wanted. But with Youth of the Beast, he found his original voice. He didn’t adhere to conventions but shot them up. Consider that the story is very similar to Yojimbo. It’s got the same premise of a stranger pitting two gangs against each other. That story was already cool, but Suzuki made it better, grittier, and dazzling. It didn’t feel like a modern rendition of a dusty samurai tale. This was the type of cutthroat rebel movie needed for that time.

And this was when rebellious Japanese cinema was heating up. There were already plenty of gritty noir films from directors like Koreyoshi Kurahara. But if Kurahara’s films like The Warped Ones and Black Sun had teeth, Suzuki’s films had colorful style. Youth of the Beast played with color. Suzuki makes the violence more vivid, hallucinations more trippy. This is a film where the smoke from a flaming car can be maroon for no reason other than it looks cool. And it does!

Suzuki’s appeal exploded after Youth of the Beast. More yakuza films followed, but also some equally gritty sexual films. 1964’s Gate of Flesh acted as a criticism of Japan’s authority through prostitution. Films about Japanese prostitution were not new at this time. But, much like Youth of the Beast, Suzuki’s film redefined the sub-genre. Gate of Flesh was bursting with style and rawness — too raw for many mainstream actresses at the time. This led to the studio hiring outsider actresses. The alternative casting added to the film’s realism. Audiences wouldn’t be thinking of flashy stars for a film set in a post-war ghetto.

After Youth of the Beast, Suzuki’s appeal exploded.

He kept making yakuza films — but now, he was also diving into grittier territory. In 1964, he released Gate of Flesh — a raw, hyper-stylized film about prostitution in post-war Japan. And while Japan had seen films on the subject before, Suzuki redefined the sub-genre. Gate of Flesh wasn’t just provocative — it challenged Japan’s post-war authority head-on. It was so raw, many mainstream actresses turned it down. So the studio hired outsider talent instead — unknown faces who made the film feel even more real. You weren’t watching celebrities. You were watching survivors in a post-war ghetto.

Making More With Less

With several breakthrough films, Suzuki was very successful in the 60s. But while the audience loved his work, the studio? Not quite. His filmmaking was becoming more rebellious and defying what the studio expected. After all, they’d been used to Suzuki making routine B-movies. Now, he was doing more of his own thing. Studio president Kyusaku Hori told Suzuki he was “going too far.” Suzuki thought he wasn’t going far enough. This led to Suzuki’s Carmen from Kawachi being even wilder with sex. Fed up, Nikkatsu would cut the director’s budget for his following films.

To the studio, Suzuki’s films weren’t just rebellious — they were confusing, risky, and hard to sell.

But the slashed budget didn’t stop Suzuki from turning out even more legendary movies.

Even with less money, Suzuki’s next film was his most revered. Tokyo Drifter was expected to be the film that would ground the director. It was posed as a reasonably routine yakuza movie. But nothing would be routine with Suzuki. He’d had a taste of exciting and stylish filmmaking. Tokyo Drifter ended up being another bonanza of the bombastic. Extra colorful, extra surreal, and extra weird. All the slashed budget did was reduce the number of fight scenes. Filling that gap was plenty of clever camera work for strange stalking scenes and executions.

Although Tokyo Drifter was a delight, Nikkatsu was still furious. So, they changed tactics. They figured if the budget wouldn’t straighten Suzuki out, maybe a lack of color would. With no wild colors for his next film, surely Suzuki would calm down. He did not. In fact, Suzuki just went from composing surrealism to the avant-garde. And he pushed it further than anyone expected.

Branded and Blacklisted

For Nikkatsu, Branded to Kill seemed like a standard movie for Suzuki. It was a low-budget, black-and-white film about a contract killer. The protagonist kills some people and falls in love. Easy stuff. Suzuki could do this in his sleep. But Suzuki wasn’t interested in dialing it back. He took his coffee, stayed up, and went crazy with this project. Many last-minute ideas rapidly changed the picture.

What started as a by-the-numbers yakuza movie transformed into a satirical surrealist picture. The violence was wild, with people being set on fire. The kills were clever, with an assassination inside a mechanical billboard. There was also plenty of bizarre sex. Only Suzuki could make a film where somebody’s fetish is boiling rice.

Loaded with strangeness and an obsession with butterflies, Branded to Kill was weird. Too weird. It was so odd that barely anybody saw it. Critics didn’t care much about either. It was the perfect time for Kyūsaku Hori to fire Suzuki. Hori was fed up with Suzuki whose films the studio deemed made “no money and no sense.”

But Suzuki wasn’t Nikkatsu’s biggest problem. The studio was facing general financial issues beyond Suzuki’s underperformance. Suzuki was the scapegoat — someone Hori could blame instead of himself.

In 1968, Suzuki was fired. In turn, he sued the studio — and after a three-year battle, won. Nikkatsu paid a fraction of what he asked for, and Hori was forced to apologize.

Sadly, this sorry arrived a little late. Suzuki’s name had been tarnished. The studio had refused to permit any of his movies to be screened. The entire Japanese film industry blackballed him for 10 years. There was still work for him on TV and with commercials. But he didn’t direct a film until 1977.

Suzuki’s status only soared since his firing. Branded to Kill became an avant-garde classic. Theaters once sparse for the film were now packed. The film once blamed for ruining a career had become one that defined it. And not in a so-bad-its-good way. More in a too-cool-for-its-time way.

Looking back on it now, this was definitely the movie the cool film students would be watching. And they were. Japanese student film groups rallied around Suzuki’s mistreatment by the studio.

In the end, Nikkatsu would fall. But Suzuki remained. The film the studio tried to bury was eventually donated to the National Film Archive of Japan — part of Tokyo’s Museum of Modern Art — as part of the legal settlement. A fitting home for a film by a director who still had more to say.

The Suzuki Resurgence

Despite being out of the game for so long, Suzuki regained his groove. But this time, the director went outside his comfort zone. Audiences were used to him making films about hitmen and prostitutes. They might not have expected him to dabble in the supernatural with Zigeunerweisen. Or comedies like Capone Cries a Lot.

Even anime was given a shot. Lupin the Third was already an anime icon by the 1980s. Suzuki added his own touch to that franchise with Legend of the Gold of Babylon. It was co-directed by Shigetsugu Yoshida but it was very much a Suzuki film. Much of the criticism was that it was too convoluted. But, yeah, that sounds like the guy who made Branded to Kill.

In Suzuki’s defense, it couldn’t have been easy for him to jump on a franchise like this. After all, the previous Lupin movie was directed by Hayao Miyazaki. How do you top a director who is pretty much Japan’s Walt Disney? Thankfully, the film has gained favor over time, like Branded to Kill. Mike Toole of Anime News Network initially hated the film. That opinion would change when he watched more of Suzuki’s works. Not to mention, Suzuki and Lupin seem like a great pairing. Lupin is an iconic anime character for being simultaneously cool and goofy. A character that fits Suzuki’s filmmaking tone to a T.

Suzuki’s rebellious spirit was exactly what Japanese cinema needed. Going from a reliable B-movie director to a chaotic auteur is quite a journey. He was never pigeonholed and never made boring movies. Yakuza and prostitute narratives never felt standard with him. Color was never drained from his pictures. Even without color, his films pop with contrast.

As a director, his style was vibrant enough to inspire the bonkers films of Takeshi Kitano. But his influence spanned across the globe. Suzuki inspired the heartfelt Wong Kar-wai and the experimental Jim Jarmusch. Tarantino himself took inspiration from Suzuki. Think about that. If it weren’t for Suzuki’s Tokyo Drifter, we might’ve never gotten Kill Bill.

Sadly, in his later years, Seijun Suzuki’s health began to decline — and directing became harder. He passed away in 2017.

But his films? They didn’t fade. Today, some of his greatest works live on in the Criterion Collection, alongside Kurosawa and Ozu. That’s not just validation. That’s legacy.

Because Seijun Suzuki wasn’t just a director. He was cool. And no matter how hard the studio tried — you can’t kill cool.