The promotional campaign for “Wuthering Heights,” Emerald Fennell’s new adaptation of Emily Brontë’s classic, arrived surrounded by rumor and speculation. Gothic whispers, ghosts, revenants haunting mind and soul, past sins returning to consume the present—these elements define Brontë’s 1847 novel, published under the male pseudonym Ellis Bell. A cornerstone of English Gothic fiction, it established a genre and inspired generations of writers to transform stories and landscapes into emotional allegories.

Fennell’s film debuted with a strategic February 12-13, 2026 release timed to Valentine’s Day, amid gossip and controversy: “It’s unfaithful.” “It betrays the novel.” Questions arose about Margot Robbie and Jacob Elordi’s chemistry, about the film’s sexual frankness—elements absent from Brontë’s more restrained prose. Meanwhile, Charli XCX’s song ‘Everything is romantic’ soundtracked the trailers, its refrain “fall in love again and again” becoming both cult phrase and effective marketing tagline, urging audiences back to theaters. In modern marketing, everything is permissible, ça va sans dire.

But what is the cinematic product “Wuthering Heights,” really? Let’s explore the unsettling, melodramatic psychology of this postmodern genre pastiche.

Incriminating Quotation Marks

Here, it was not so much the book that proved fateful (as Dante Alighieri said), but the quotation marks that accompanied it. Everyone noticed the prominent quotation marks framing the title “Wuthering Heights” on the official posters. It wasn’t accidental, but a deliberate choice. Fennell, who also wrote the screenplay, never intended to translate Brontë’s words into images in a literal or dutiful manner.

What we get is an unfaithful, hybrid adaptation that plunders the novel for what it needs, transforming into flesh characters, thoughts, subtexts and unspoken tensions already present in the original. Bringing the entire narrative to screen would have been ambitious, perhaps self-defeating, given contemporary cinema’s norms and shortened attention spans. Film runtimes expand without regard for classical screenwriting ratios, while audiences increasingly prefer serialized formats—episodic structures with compact or weekly releases, sometimes split into two “chapters.”

To recount the dramatic events of Catherine, Heathcliff, Edgar Linton and Isabella, and then of their heirs Linton, Hareton and Cathy, would have required more time, further development, and effort to disentangle a novel once described—upon its publication—as a matryoshka for its narrative structure. Multiple timelines. A rich and baroque fresco of characters, voices and faces essential to the unfolding of the story. Two alternating narrators, Nelly and Mr. Lockwood. Wuthering Heights, the novel, is a stratified world. Cinema, by contrast, is generally the realm of mainstream entertainment, ready to sacrifice complexity on the altar of accessibility. How, then, to proceed?

Emerald Fennell chose the most fitting path, and perhaps also the most pragmatic one. To plunder the novel, to take what her vision required in order to nourish itself, and then to assemble her own mosaic. All without sacrificing a personal style that ultimately shaped the aesthetic and formal decisions of the project.

Postmodern Melodrama

“Wuthering Heights,” the film, is a pastiche in the best sense of the term. A creative amalgam born from the contamination and interweaving of genres and styles. If you seek verisimilitude, narrative coherence, and strict realism, Fennell’s film may not be for you.

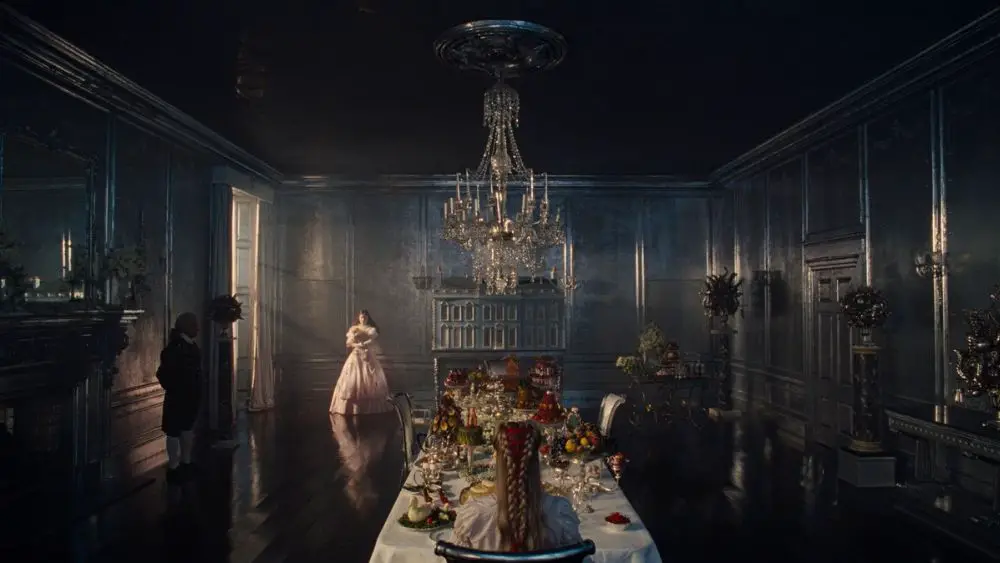

Every visual choice emerges from a precise imaginative framework, constructing an entire universe through baroque, redundant, almost operatic excess, in which artifice triumphs and melodrama reigns. The settings, compositional balance, aspect ratio—everything evokes lucid dreaming, that suspended state between sleep and wakefulness guided by unconscious emotional imagination.

The color palette is bold and saturated: reds and whites, nocturnal blues, the leaden darkness of Wuthering Heights against moorland. Primary colors, stark light and shadow, theatrical lighting married to Caravaggesque dramatization. Yet all this sits within an ultra-pop, Instagram-ready framework born of contemporary postmodernism. Amid the relentless barrage of content bombarding daily life, Fennell’s work continues the stylistic trajectory of Promising Young Woman (2020) and Saltburn (2023). She doesn’t pursue meticulous historical reconstruction in the Visconti or Zeffirelli tradition, but rather emotional impact—feelings powerful enough to overwhelm spectators while satisfying visual appetite.

Horror vacui (the Latin term meaning ‘fear of empty space’) speaks directly to the unconscious and to the protagonists’ emotional states, ultimately shaped by them. Once again, we seem suspended in the dimension of dream. The landscape is born from the inner world of the characters, particularly Catherine and Heathcliff, from the darkness of their desires rather than from objective reality. The decaying manor of Wuthering Heights rises amid dark and threatening mountain formations; the fog-wrapped moors become lands of ghosts and whispers; houses creak, haunted by the past and by the horrors perpetuated by fathers. All except the Lintons’ residence, which appears to have stepped out of an illustration from The Secret Garden.

In various interviews, the director has stated that she and producer Margot Robbie always conceived this adaptation of Brontë as a contemporary classic for new generations, citing romantic blockbusters such as Titanic, The Notebook, and Gone with the Wind as inspirations and points of reference. A taste for vintage melodrama permeates the final product, with moments that openly nod to the genre’s classics through sets, backdrops, gestures, and behaviors seemingly “borrowed” from that aesthetic canon.

Drawing extensively from the 1940s and 1950s Hollywood, “Wuthering Heights” doesn’t seek to unsettle—it seeks to overwhelm. It abandons emotional realism to indulge in baroque excess, where images amplify emotion, functioning as a megaphone rather than as allegory. The imagery doesn’t suggest, it intensifies what the characters feel and, by extension, what audiences experience.

The Law of Desire

Without venturing into spoilers, let me say: Wuthering Heights‘ opening moments make a programmatic declaration. What the audience is about to witness is not merely a love story; it is a work about desire. And about its unconfessable shades.

Carnal, unwanted, toxic, sensual and sexual, difficult to admit and even harder to manage: missed actions destroy more than love itself. For this reason, the film cannot be reduced to a conventional love story between two human beings consumed by passion. The destruction of the universe born from Catherine and Heathcliff’s encounter arises from rejection and obsession, from the thirst for redemption and revenge, from jealousy, and finally from those missed acts that devour the flesh until nothing remains but the murmurs of weary ghosts.

The opening, seemingly disorienting, in fact contains the very essence of the film and stands as the most overtly Gothic segment of the entire project. It presents the nightmarish childhood, or perhaps the nightmare of childhood, of its young protagonists, already marked by destiny. As the story progresses alongside their growth, another detail emerges: nearly all the characters behave as though afflicted by traumatic neuroses, children who never fully matured, trapped in unresolved dramas. In adulthood, they act from a chronic infantilism, incapable of growth or transformation, paralyzed within a traumatic neurosis destined to repeat itself again and again, without redemption or release.

For this reason, for instance, Catherine’s transition from a “before” to an “after” as a married woman appears less evident than in the novel, perceptible only on a formal, aesthetic level. In truth, she remains that wild moorland child, playing at love without understanding the dangers of the adult games.

The same applies to her bond with Heathcliff: united since childhood by shared destiny, condemned to identical traumas. Absent parents, surrounding death, an exclusive bond that saves and a dependency that heals. They grow within this wounded, traumatized perspective, incapable of opening to others even as young adults. Unable to untangle their neurotic relationships’ knots, they’re condemned to relive the same patterns eternally. Both lack tools to understand and heal their traumas, to evolve. Their narrative arc unfolds within the parameters of neurosis, of the missed act that becomes obsession, transforming into a toxic and dangerous game as stakes rise.

Infantilism also links the protagonists to Nelly and Isabella Linton, Edgar’s protégée, portrayed by Hong Chau and Alison Oliver. Nelly lives in a conflicted bond with Catherine “Cathy,” fulfilling her role as companion, noble-born but fallen, while restraining her jealousy and envy within rigid composure. She longs for Catherine’s place and, in attempting to protect her, ultimately wounds her, distancing her from her true nature and genuine desires. She’s equally trapped by traumatic neurosis, unable to break the behavioral pattern that drives her to repeat the same mistakes.

Isabella, by contrast, is a young woman suspended in a state of perpetual childhood—bows in hair, dollhouses, naïve thoughts, and an accommodating disposition rendering her vulnerable prey.

Heathcliff, by contrast, seems to shed some of the novel’s more threatening and dangerous traits, tempering the desire for revenge born of rejection. If he cannot have Catherine, no one shall. Love becomes ardent, frustrated desire before mutating into obsession. In this “Wuthering Heights”, the Gothic dimension is more sentimental than visual, confined to aesthetic brushstrokes and fleeting moments, flourishes of Fennell’s signature as she grapples with adapting this British Gothic cornerstone.

Every Love Story Is a Ghost Story

Borrowing, albeit somewhat improperly, the title of David Foster Wallace’s biography allows us to enter more directly into the film’s essence through a literary spark: every love story is a ghost story, even when those ghosts do not haunt ancient mansions or fog-laden moors, but rather storm-tossed souls. The quotation “whatever our souls are made of, his and mine are the same” (lifted from the novel) becomes both emblem of salvation and damnation, original sin and convenient alibi for toxic behavior, attraction unfolding into a paso doble of love and hatred locked in a single embrace. Opposites and oxymorons sketch the contours of the entire “Wuthering Heights” operation, ultimately narrating a grand story of and about desire, a subject too often diminished because of its inevitable carnal implications.

In this new adaptation, flesh is no mystery. It’s an obtrusive physical presence seeking space, literally incarnating from an emotional dimension into a corporeal one. With minor spoiler: the “famous” skin room offers a striking example: a bedroom faithfully reproducing Catherine’s skin, color, softness, freckles included.

Every detail—the recurring food transformed into metaphor, allegorical elements, specific visual motifs—evokes something beyond itself in the viewer’s mind, configuring as objective correlatives of unconscious emotion. Desire manifests itself not first through the sexual act, but through a sensory awakening that defines the contours of the entire project, legitimizing its dramaturgical choices and its unfaithful transgression of the source material.

Shifts in tone openly court genre, traversing the many nuances of Hollywood’s Golden Age: banter worthy of screwball comedies, sweeping sentimental melodrama, unsettling Gothic touches, even flashes of imagistic body horror. The film becomes a journey into a derivative universe shaped by Fennell’s hyperactive imagination. It is an opportunity to explore themes and nuances through betrayal, climbing among signs, references, citations, and objective correlatives into territories still often considered taboo—rarely addressed with such bold intelligence.

The chemistry between Margot Robbie and Jacob Elordi proves essential. Despite casting controversies, both actors embody their generations—Millennials and Gen Z—with a cinematic beauty that recalls Hollywood’s golden age. Rather than disappearing into these imposing roles, they find interpretative keys that unlock their characters’ unconscious depths. Catherine and Heathcliff are, essentially, kindred souls—unloved children who found in mutual protection and companionship their only way of existing. Trying to resurrect their past after years apart ends in failure, propelling them toward a tragic finale. A final act that legitimizing the escalating pettiness, psychological, physical and emotional torment, jealousy, cruelty transforming Wuthering Heights into a dark tale.

In this film, nothing is left to imagination. Everything is revealed onscreen, risking stimulus overload for both brain and fantasy—that faculty always ready to fill gaps and construct worlds. The dynamic recalls horror cinema. Pleasure and fear have long been two sides of the same coin. When the monster appears, horror is unveiled. Precisely then, fear begins dissipating, along with adrenaline. Emotion passes through the invisible, through darkness onto which monsters and fantasies are projected, compelling imagination to do the rest, filling voids.

The result is an audiovisual work where everything is shown, pursuing emotional and visual shock, building scene after scene, frame after frame, a dialogue between past and present, ferrying a classic into absolute modernity. By choosing Charli XCX to shape the soundtrack. By betraying historical verisimilitude for personal, fantastical postmodernism. By transgressing rules and conventions. Again and again.