If someone had said Zootopia 2 would answer, definitively and unequivocally, whether The Shining—released forty-five years ago—still holds up, I would have thought they were joking.

But it does. More on that in a moment.

Obsessions—or hobbies that turn into deep, dark rabbit holes—often have murky origin stories.

Mine, however, is crystal clear, and it is, by her own account, entirely my mother’s fault.

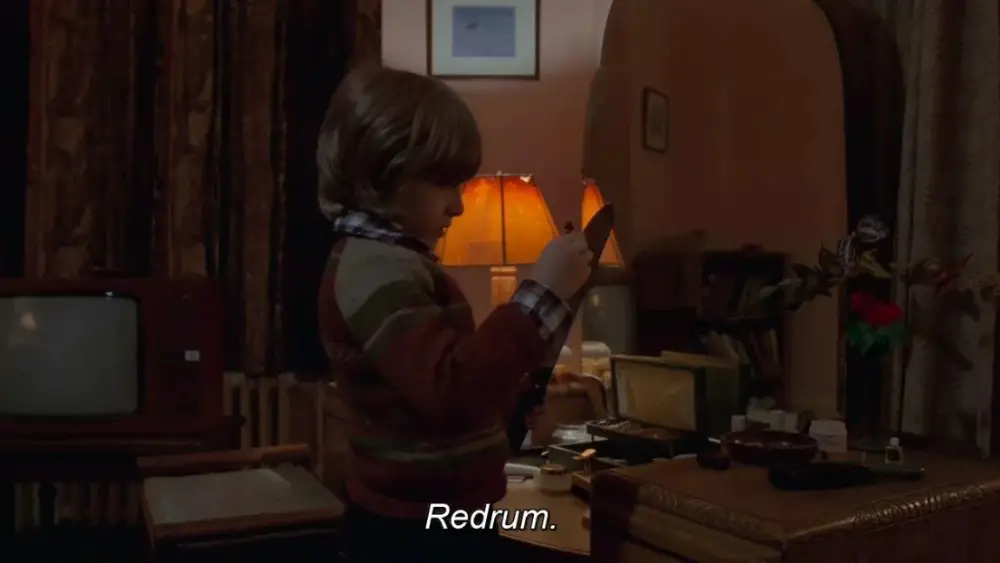

One morning, when I was at the tender and impressionable age of nine, she started a seemingly innocent conversation over breakfast. She told me, clearly enjoying the memory, how she and her siblings had once seen a scary movie called The Shining. In torrid detail, she described how they covered their eyes as blood poured from elevators, covered their ears as the epic soundtrack underscored images of dead twins in endless corridors, and, worst of all, she reenacted the Redrum scene—crooked finger and eerie voice included.

The still-developing synapses of my nine-year-old brain rewired instantly. Not only did I struggle to sleep for the next year or so, I also had to deal with the uniquely horrifying experience of my mother, who had raised me with impeccable care and love in every other respect, performing a demonic child’s voice.

But fear, it turned out, was only the beginning. Like Moses standing before the Red Sea, I saw a clear path open up. At its entrance stood a dark, blood-soaked sign: “No turning back”. I stepped through without hesitation. Instead of trying to numb the fear, I fed it, devouring every single Stephen King novel I could get my hands on, and, in the process, acquiring a lifelong interest in books and movies.

Only later did I come to recognize this for what it was, an unintended but enduring gift.

So, when, after thirty-seven years of reading about, rewatching, and discussing The Shining with anyone who seemed even mildly interested, the chance came to see it for the first time on a giant IMAX screen, I knew a pivotal moment had arrived.

Ironically, it was my ten-year-old son who pointed it out. On his way to a relatively age-appropriate scary movie with a friend, he mentioned seeing The Shining poster in the theater, one he recognized from the Overlook Hotel poster hanging in our living room.

A quick search confirmed a special screening—two days only—starting at the profoundly midlife-unfriendly hour of nearly ten o’clock at night. Detailed planning ensued. A budding flu was neutralized with an excess of vitamins. A rare opportunity for a strategic nap was seized.

Two friends, similarly persuaded, came along.

I was eager to see the film again; it had been a few years. Still, beneath that excitement lurked a sense of trepidation. How would it hold up on a giant screen? Would I notice flaws that might dampen the magic?

Those fears dissolved within seconds.

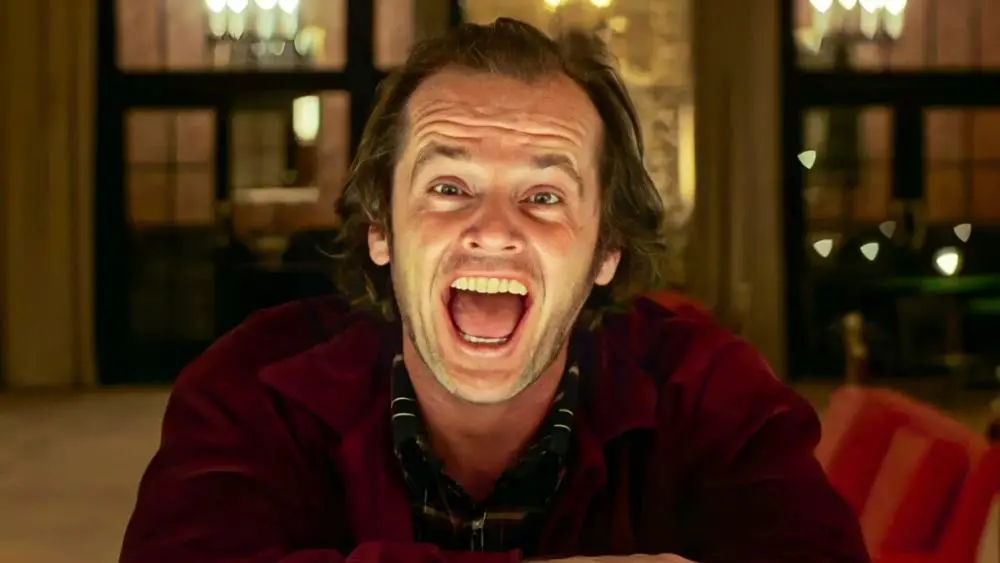

The opening scene was exactly as I remembered it, absolutely perfect. The relentless score, the sweeping aerial shots inviting us into a nightmarish journey, and the initially restrained performances by Jack Nicholson and Shelley Duvall immediately reassured me. This was going to be exactly as it should be.

So what makes The Shining still feel perfect?

First, it is not a product of its time. Many films, even great ones, are firmly rooted in their era, capturing a cultural or political snapshot that defines their appeal and drawing strength from their contextual resonance. The Shining, in contrast, remains timeless, unfolding beyond style or period.

Much has already been said about Stanley Kubrick’s visual perfection, so I will leave that ground well covered. Still, it’s a joy to watch a visual style in which sound and space are merged with such care: calm, precise, and entirely in service of the story, especially in a time when sensory overload is often confused with dramatic impact.

Kubrick does not just direct his actors; he directs his audience. He shows us exactly what we need to see, employing extreme close-ups or long, deliberate tracking shots when necessary, while leaving just enough room for interpretation. Each viewing reveals new forms of foreshadowing, even after decades of familiarity.

And then there is the acting.

Not just Jack Nicholson, whose performance, if you look past the sheer physicality and the famous “Here’s Johnny” moment, is marked by tiny expressions that become a movie of their own. A fleeting smirk, a slightly raised eyebrow, or a drifting gaze all quietly deepen our sense of unease. Nor Daniel Sidney Lloyd, who set a benchmark for child acting that would not truly be matched until The Sixth Sense nearly two decades later.

The absolute sine qua non, however, is Shelley Duvall.

Often under-appreciated and mocked at the time, she now seems perfectly cast. Her performance, once dismissed as emotional imbalance, emerges as the film’s emotional and rational center—the performance the audience holds onto.

Are there flaws? A few. A racial slur is uncomfortable, and the “spermbank” reference feels blunt rather than unsettling. Even the extended final sequence, replete with spider webs and skeletons, feels unnecessary after the film has already delivered its iconic elevator scene.

However, these details are forgivable precisely because they’re so rare, and their obsolescence only underscores how little else in the film belongs to its time.

Which brings me back to Zootopia 2.

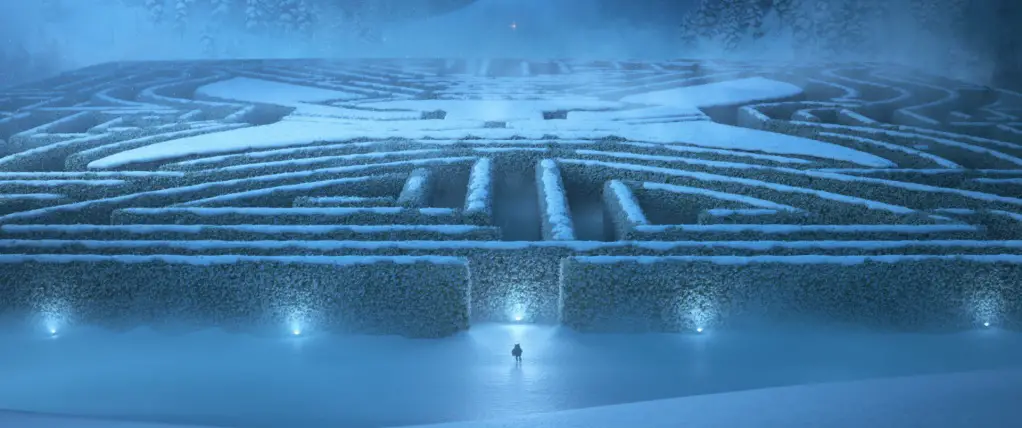

Less than twenty-four hours after watching The Shining, my wife and I took our two young sons to see it. Toward the end of the film, quite unexpectedly, the unmistakable trumpet motif from The Shining echoed through the theater. What followed was a complete homage: a labyrinth chase, rage-fueled limping through the snow, even a reimagined role for the snowmobile.

A still from Zootopia 2

What strikes me is not just that the film overtly references The Shining, but that it does so without parody or exposition. It simply assumes its audience—children born decades after 1980—will register the rhythm of the chase, the geometry of the maze, the menace of a single figure limping through the snow. My 10-year old, who has never seen Kubrick’s film, leaned forward. The tension worked on him purely through visual grammar.

That’s when I understood: The Shining‘s power isn’t locked in its original context. Its formal language—the steadicam tracking, the geometric spaces, the methodical build of menace—has become so foundational that it can be lifted entirely into a children’s film and still function.

It’s telling that Disney, a studio famously protective of its legacy, would choose The Shining as a reference point. Yet it trusts that imagery from an adult horror film can be (safely) repackaged for a family audience.

The reason is simple: The Shining doesn’t endure because of shock value, but because its mastery of sound, space, and visual rhythm remains clear and compelling decades later.

In that sense, the homage is not simply proof that The Shining is being remembered, but that it has become architectural—no longer confined to 1980, or even to the horror genre itself, but absorbed into the common language of film. When a studio can assume that children will instinctively understand the dread of a maze chase they’ve never seen before, that’s not nostalgia. That’s cultural permanence.

Watching Zootopia twenty-four hours after The Shining felt unexpectedly perfect. It confirmed what I’d suspected during that late-night IMAX screening: Kubrick didn’t just make a horror classic. He built a labyrinth that filmmakers have been trying to escape for forty-five years—and most still end up lost in the snow.