From The Shawshank Redemption (1994) to 1917 (2019), here’s a look at some of the most iconic shots from Roger Deakins movies.

One of the most influential and highly regarded cinematographers today, Roger Deakins is a master of lighting and composing rich, painterly shots. He works to serve the story’s requirements rather than impose his own style. It’s why he has been able to easily collaborate with great filmmakers and be part of groundbreaking projects.

Born May 24, 1949 in the UK, Roger Deakins is the son of a construction worker and an actress. He graduated from Britain’s National Film School, and started his career as an assistant cameraman in the 1960s on British television documentaries. Later in the 1970s, he moved to Canada and joined the National Film Board of Canada to shoot documentaries all over North America. Roger Deakins debuted as a cinematographer in feature-films, starting from Michael Radford’s 1984, an adaptation of George Orwell’s popular dystopian novel.

He worked in critically acclaimed movies like Sid and Nancy (1986), The Long Walk Home (1990), and Homicide (1991). Then arrived the opportunity to collaborate with Coen Brothers in Barton Fink (1991), the first of many. Over the years, Deakins became the most sought after cinematographer working in Hollywood. From Shawshank Redemption to Sam Mendes’ 1917, Deakins has been nominated a whopping fifteen times for Oscars, winning twice. Here’s a look at some of the iconic shots conjured by the master craftsman.

Best Roger Deakins Shots

1. The Melancholic New York City, Sid and Nancy (1986)

This is one of the earlier works of Deakins which proved that he is a wizard behind the camera. Alex Cox’s Sid and Nancy is a grim, biographical tale of Sid Vicious, the bassist for British punk rock band Sex Pistols, highlighting his troubled relationship with girlfriend, Nancy Spugen in New York. The temperamental couple gradually spiral down as they are caught in the clutches of drug addiction. Deakins went for a more verite style, observational and documentary-like, to closely capture the volatile energy between Sid and Nancy.

Nevertheless, Deakins finds some beauty even in the most decrepit situations, for instance, the shot where Sid and Nancy kiss in a garbage-filled street. But the stand-out moment in the film is the long-shot of Sid standing amidst the cloudy New York landscape. The somber atmosphere perfectly conveys the character’s melancholy and agony as his dreams are crushed in the depths of drug addiction. Clouds are one of the prominent elements in Deakins’ cinematography. Here in this master shot it reinforces the particular mood of pensive sadness.

WATCH: 11 Stunning Examples of Visual Storytelling

2. The Hallway, Barton Fink (1991)

Though Roger Deakins has lent his talent to a wide-range of filmmakers, he is the go-to cinematographer of Coen Brothers. And their fruitful collaboration began with the 1991 satire Barton Fink. Coen Brothers are best known for crafting darkly comic misadventures of men. In Barton Fink, the protagonist is a renowned playwright, who is recruited by the Hollywood machine to write a populist script. Barton moves to a hotel room and as the demands of the job adversely impact the man’s psyche, the claustrophobic aspect of the setting is also amplified.

Deakins repeatedly focuses on the hotel’s wallpapered hallway to gradually build up the unrest. Eventually, it ends with an eerie and explosive shot of a flame-filled hallway. The ominous shot of the hallway also bears some resemblance to Kubrick’s The Shining. The hallway was a set. In order to augment the lighting set-up, Deakins cut holes behind each of the wall sconces to have more light source than just the practical lamps. Deakins also states that they built two identical sets of the hallway. They burned down one for the final scene by filling it with gas through the perforated wallpapers.

3. Andy’s Liberation, The Shawshank Redemption (1994)

Frank Darabont’s Shawshank Redemption is an example of a simple story told in a deeply resonant manner. And one of the primary reasons for the prison drama’s timeless feel is Roger Deakins’ subtle camera movements and framing. In fact, the visual storytelling reaches its high when the wrongly imprisoned protagonist Andy Dufresne succeeds in his escape plan. There’s the iconic, symmetrical overhead crane shot of Andy standing in a large field, arms outstretched during the rainstorm.

Andy finds his freedom after crawling through miles of sewage pipe. The tightness of the frame in that scene, followed by the free and reborn image of Andy perfectly conveys the character’s euphoria. Deakins has mentioned that Andy’s escape scene had more details. It included him running across the field to catch a train. But due to a tight schedule they had to plan this shot of shirtless Andy in a lightning-lit rainstorm. Interestingly, this emotionally stirring composition was strongly embedded into our consciousness.

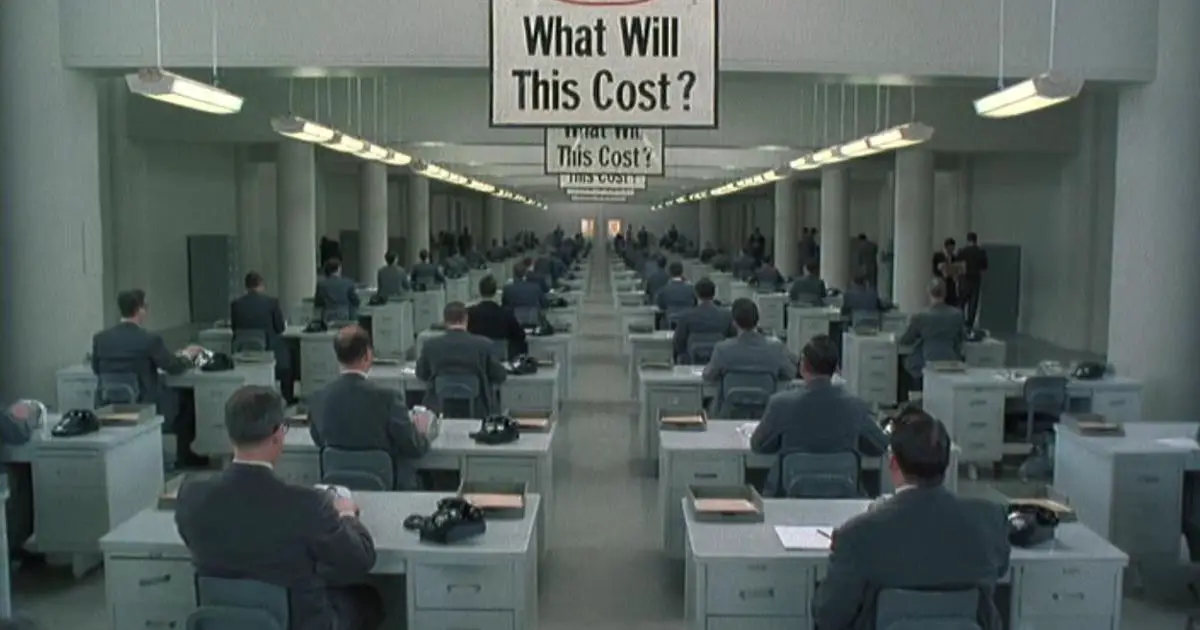

4. The Office, The Hudsucker Proxy (1994)

The Hudsucker Proxy is one of the underrated films in Coen Brothers’ oeuvre, featuring distinct and meticulous cinematography by Deakins. The narrative is set in 1950s Manhattan, and largely unfolds inside the massive offices of Hudsucker industries. The film is a darkly comic parable on greed, and the Coen Brothers envision this old New York as a mythical landscape. Hence, production designer Dennis Gassner and DoP Roger Deakins crafted a cityscape of tall skyscrapers using miniature buildings and well-planned motion control photography.

One important sequence where the art department and cinematography brilliantly come together is when the Coen Brothers take us through the narrative’s corporate work environment. The office space is huge, bland and yet intimidating since it conjures a Kafkaesque vision of bureaucratic nightmare. Another impressive and innovative moment is the ‘Hula Hoop’ scene. Released in the same year as The Shawshank Redemption both the movies turned out to be box-office failures. Nevertheless, in the later years Deakins’ visual creativity was acknowledged.

5. The Great White North, Fargo (1996)

Coen Brothers’ Fargo tells an outlandish tale laced with dark comedy. It was set in a dry small-town with blinding white vistas. Deakins calls Fargo’s aesthetic ‘simple by design’, since it was a low-budget film made in the wake of Hudsucker Proxy’s commercial failure. Yet Deakins’ cinematography is absolutely rich even within the simple setting. Moreover, Deakins’ visuals attach a sense of irony and fatalism to the proceedings. The feeling is particularly evoked during the haunting moment of Steven Buscemi’s character burying a briefcase full of money in a vast and banal field of snow.

In fact, Deakins’ cinematography avoids overt cinematic flourishes in favor of a straightforward visual representation. He swiftly immerses us into the characters’ horrifying reality. Deakins mentions that there was very little snow during the shoot. A lot of the snow had to be added manually, sometimes using an ice-chipping machine. The shoot was also stalled when there were bright blue skies, since Deakins wanted to avoid that kind of light.

6. Looking at the Himalayas, Kundun (1997)

Kundun marks the only collaboration between Martin Scorsese and Roger Deakins. It earned the cinematographer his third Oscar nomination. Deakins is of the opinion that Scorsese hired him for the movie due to his early experiences in documentaries. Moreover, Deakins’ documentarian’s eye has perfectly captured the epic scenic beauty in movies like Mountains of the Moon (1990). Kundun is centered on the early life of the Dalai Lama until his exile from Tibet.

It’s a film about observation, faith and yearning. And this is beautifully and robustly expressed during the final moments of the narrative when the young Dalai Lama looks at the vast Himalayas through a telescope, seeking his home. For both Scorsese and Deakins, Kundun is a departure from the kind of films they usually do. It doesn’t possess many kinetic camera moves. For the most part, including the telescope scene, Deakins simply relied on natural light, and elsewhere in the monastery scenes he infused a more naturalistic look by utilizing practical sources.

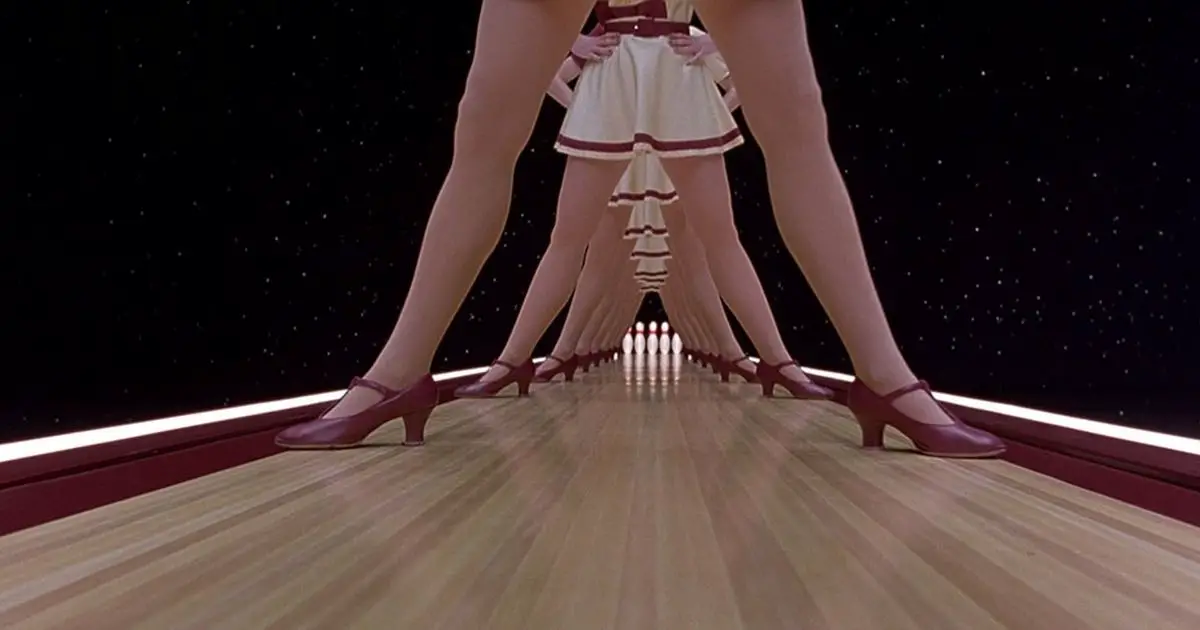

7. The Trippy Dream, The Big Lebowski (1998)

Coen brothers’ cult classic revolves around a lazy Los Angeles guy who hangs around a bowling alley. He gets mixed up (better word? Caught up?) in a case of mistaken identity and consequently problems follow him around. One of the standout sequences in Big Lebowski is the trippy and hilarious dream sequence where Jeff Bridges’ Dude dances with Julianne Moore’s character while dancers wearing bowling-pin headdresses are seen in the background. Another memorable shot in the sequence is the perfectly symmetrical under-the-leg shot of a bowling lane.

This dream sequence is unique since it has a stylized look unlike the real and simple aesthetics seen elsewhere in the narrative. Coen brothers’ — stern taskmasters — in fact storyboarded the look and feel of the scene. Deakins makes it more playful and high-key, pushing us to compare it with energetic song-and-dance numbers from the classic musicals. It was also one of the most highly lit sequences in the cinematographer’s filmography as the set here is very bright and white. Deakins calls it “the most weird, strangest shoot.”

8. Escape from a Chain Gang, O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000)

The Coen brothers’ crime comedy feature, set in the Depression-era Mississippi, is an absolute visual delight. In order to achieve story-book texture, the film was said to be extensively color-corrected during the post-production process. In fact, it was one of the very first films to go through such an elaborate process. Deakins shot the footage on film, and then transferred it to digital to create the sepia-tinted, dusty aesthetic style of the 1930’s Deep South. Once the correction was done, it was re-transferred to film. The result was a totally immersive experience which pulls you in right from the title sequence when the three zany and foolhardy convicts escape from a chain gang through a prairie field.

Deakins mentions that they ‘wanted a kind of feeling of a painted postcard’. While digital technology was used to do certain effects at the time, the cinematographer worked for nearly 11 weeks to rework the color on the whole film. Later, it became a common method in the post-production process.

9. Reasonable Doubt, The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001)

Coen Brothers and Deakins go to 1950s Americana to craft this tale of murder and deceit. The film’s gorgeous black-and-white cinematography with smoke-filled frames pays ample tribute to film noir aesthetics. In fact, the movie was filmed in color and then printed in black and white through a special processing method. The overtly stylish atmosphere perfectly works in tandem with the monochrome. This was particularly evident when the defense attorney delivers a monologue in the interrogation scene, while a bright ceiling light refracts through the chamber.

The shot also looks like a brilliantly crafted homage to top-notch noirs like Citizen Kane (1941) and Sunset Blvd. (1950). Nevertheless, unlike in film noir, Deakins didn’t use few light sources to turn the characters in the room into a silhouette. The characters are in sharp focus, and Deakins made it possible by keeping a truss above, and bounced off a row of lights from this truss. The result is a foreboding, picturesque, and dynamic scene.

10. Night-time Shootout, No Country for Old Men (2007)

No Country for Old Men is a dark neo-Western that revolves around a hunter who discovers a suitcase full of money in the Texas desert. Soon, a psychopathic hit man is on the trail of the hunter to retrieve the money. Deakins’ early establishing shot of the desert and the carnage related to a drug deal gone wrong is remembered by most viewers. But Deakins takes bold steps in the night-time sequences, particularly during the earlier shootout and chase scene that unfolds in the backdrop of contrasting natural colors.

Deakins mentions that these are the most challenging and terrifying scenes where the final look of it is hard to think about until shooting in the night. The menacing angle in which the silhouetted-shooter is shot along with the truck headlights amp up the atmosphere of dread. Moreover, the way Deakins lights and shoots the chief antagonist Anton Chigurh turns him into a pure representation of evil. Deakins got an Oscar nomination for his work here though he lost it to Robert Elswit for his phenomenal work in There Will Be Blood.

11. The Great Train Robbery, The Assassination of Jesse James by Coward Robert Ford (2007)

Andrew Dominik’s revisionist Western contains one of the most expertly constructed hallmark shots of Deakins. This is one of the final projects where Deakins shot on film before making the digital transition. The scene showcases outlaw Jesse James and his crew robbing a train in the night. Smoke and shadow swirl as the slow passing of the train’s headlight unveils the hooded robbers hiding in the woods. There’s a brilliant addition of extra color textures to ink-black atmosphere. Finally, Jesse James coolly walks away from the light, which elevates him into a mythical Western hero as he is often portrayed.

Deakins used a dolly for these shots, and impressively cuts away from the wide-frame to tall trees, quiet faces, and so on. However, the most mesmerizing aspect of the iconic shot is the great use of lighting. Since a real train’s headlight wouldn’t bestow such an effect, Deakins used a 5K Tungsten par lamp and mounted it on a motorized flatcar. The shot is a perfect amalgamation of all the cinematography elements.

12. Revolutionary Road (2008)

Apart from Coen Brothers and Denis Villeneuve, Roger Deakins has also frequently collaborated with Sam Mendes. Revolutionary Road, their second collaboration, is an adaptation of Richard Yates’ renowned 1961 novel. It’s a critique on the mundanity of 1950s American suburban life. Deakins settles on a visual style for this domestic drama that’s piercingly simple and clear. Mendes decided to shoot on location, and with few exceptions, in continuity. Since this is an interior drama of a marriage falling apart that revolves around the Wheelers (played by DiCaprio and Kate Winslet), the shooting strategy facilitated the actors to attune themselves to characters’ psychology.

Deakins, who’s always adapted himself to the requirements of the story, rightly captures the heated, claustrophobic atmosphere of a real house. Some of the brilliantly observational moments are when the camera looks at the very still April Wheeler (Winslet) with a cigarette in hand. The background is out-of-focus and Deakins’ tense framing conveys the agitation in April’s mind. It’s a purely subtle moment which zeroes-in on one’s emotional crisis.

13. The Dinner, Doubt (2008)

John Patrick Shanley adapted his own play Doubt into a movie of the same name. He recruited Roger Deakins to fit the tale into the cinematic medium and the cinematographer facilitated the smooth transition from stage to screen. From using Dutch angles to lines bisecting the frame, Deakins attaches an air of ambiguity over the central tense conflict between the charming parish priest Flynn and the displeased Sister Aloysius. Deakins filmed Doubt at a real-life convent in the Bronx. Staying true to his unobtrusive style, the cinematographer did six-week prep before the shooting.

Doubt is an intense emotional drama, and similar to Mendes’ Revolutionary Road it’s all about capturing the emotional dimensions of the characters. Deakins does a great job, especially in observing the unwavering Aloysius (played by Meryl Streep). Even in the above dinner scene at the convent, Deakins blocks and lights the space to focus on the dismal atmosphere as presided over by the stone-faced Sister Aloysius. Doubt proves that Deakins’ work can be refreshingly straightforward yet impart a certain depth to the proceedings.

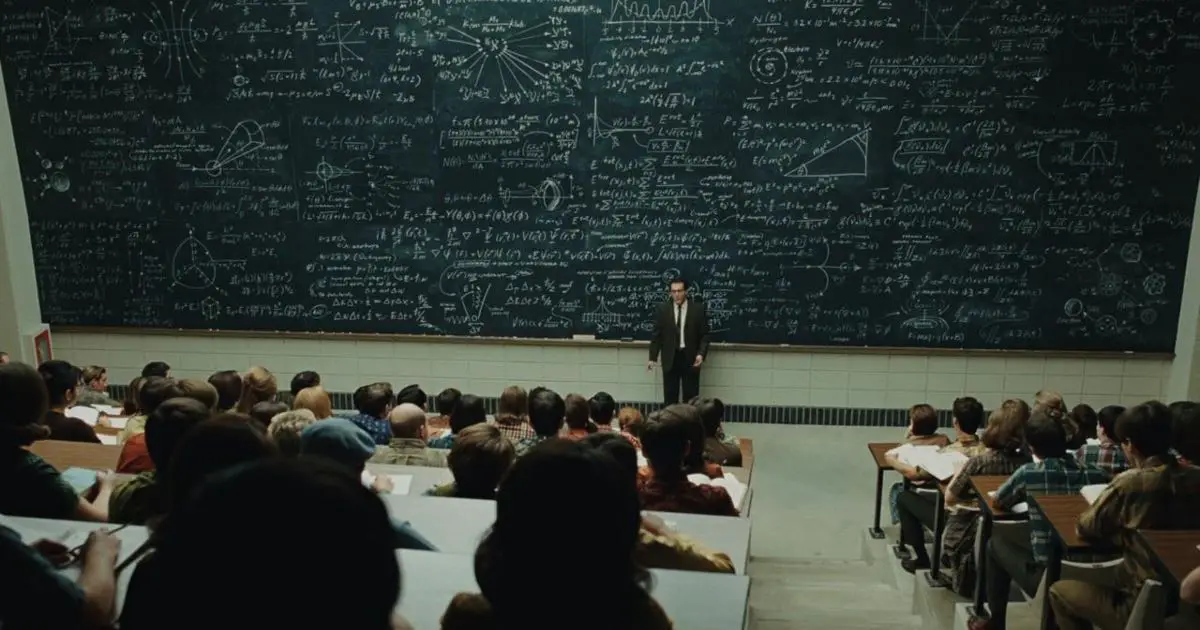

14. The Chalkboard and Lecture Hall, A Serious Man (2009)

Coen Brothers’ A Serious Man is a dark comedy and an existential drama which revolves around a 1960s American Midwestern physics teacher, Larry Gopnik who belongs to an anxious and sterile suburban community. The narrative follows Larry’s seemingly simple journey to figure out why he is cursed by such terrible luck and misery. Larry’s crisis unfolds like a complex equation which is better exemplified by the lecture hall and a blackboard bearing physics equations. Moreover, this was a dream sequence where Larry’s alleged nemesis eventually pushes him against the blackboard.

The key shot of Larry standing against the giant board perfectly hints the otherworldliness of the scene. Deakins primarily used HMI window lights to light the lecture hall. The cinematographer also mentions that since the hall didn’t have much space for ‘lighting balloons’, he rigged white fluorescent lights plus key flood light, known as Red Heads, to serve their purpose. The result is a bright and sterile atmosphere that somehow retains a surrealistic or nightmarish quality.

15. The Gorgeous Landscapes, True Grit (2010)

Coen brothers’ True Grit is an inventive remake of the 1969 John Wayne Western classic. Deakins’ glorious wide-screen shots of the rugged landscapes bring to mind the John Ford classics like My Darling Clementine (1946) and The Searchers (1956). At the same time, Deakins emphasizes on the harshness and perils in the landscape, which isn’t far removed from his showcase of Texas landscape in No Country for Old Men.

Deakins states that for True Grit he wanted the landscape to resemble one in a kids’ adventure story. It’s largely because the film unfolds from the perspective of Hailee Steinfield’s revenge-seeking 14-year old protagonist. The film also features another scene that bears the hallmarks of Deakins’ cinematography. This was the courtroom scene where we meet Jeff Bridges’ character Rooster. Sunlight flows through the lower part of the blinds in the windows with Rooster at the center of the staging. Alongside Deakins’ shooting strategy for landscapes, this brilliantly stylized moment conveys why Deakins is the most creative cinematographer.

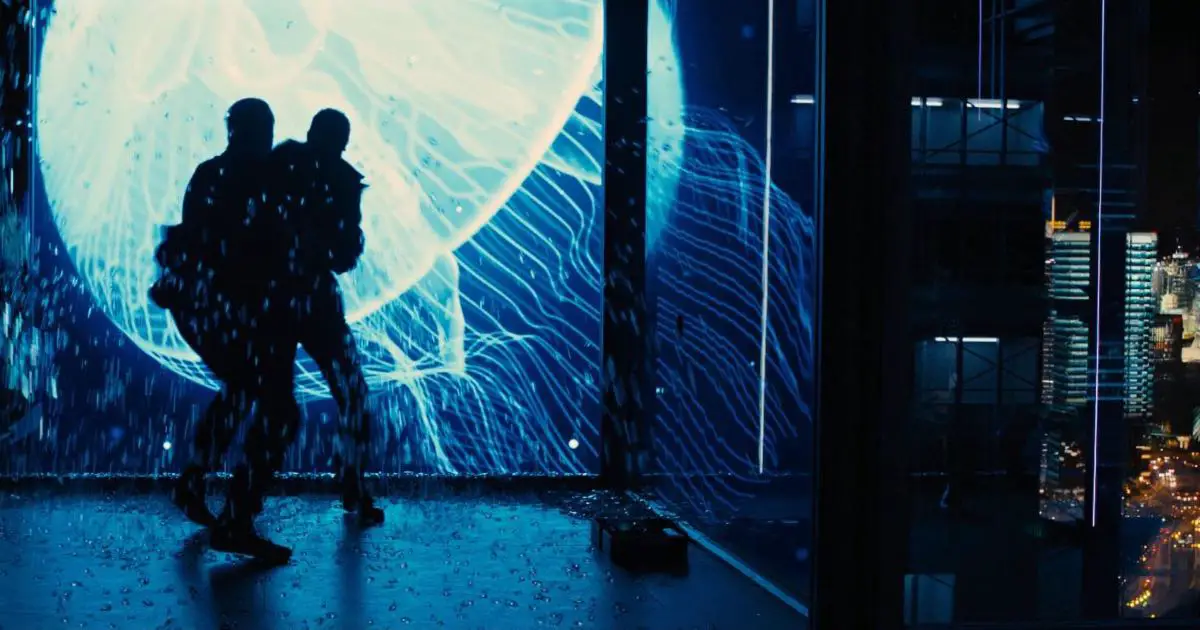

16. The Glass Tower, Skyfall (2012)

Roger Deakins re teamed with Sam Mendes for the Bond movie, and the British cinematographer got the opportunity to work in England after The Secret Garden (1993). Skyfall was also the first Bond film to be shot digitally. In one of the key action scenes, 007 follows an assassin through the empty, dark offices of a Shanghai skyscraper. Bond monitors the assassin’s movements while the glass panels of the office reflect the images from the nearby big electronic billboards. When the action reaches a crescendo – the fight shot in silhouette – the color changes to neon blue and a jellyfish floats through the glass panel frame, bringing forth a sense of modernism and exoticism to a simple cat-and-mouse action scene.

Deakins came up with the idea of using vast billboards as a source of light for the whole set. Mendes and Deakins felt that would capture the metropolitan feel of Shanghai. But before executing the idea, Deakins was involved with an art department to build a model of the set in order to determine the right camera angles and lighting set-up. Besides, he did ample research on the type of large LED screens that could serve as billboards.

17. Loki Hears the Whistling, Prisoners (2013)

Roger Deakins is often so much in tune with the story that’s told. In other words, his own artistic vision becomes one with the filmmaker. This is particularly the case with Denis Villeneuve’s gripping kidnapping mystery which features a bunch of morally gray characters. The narrative is full of intense, high impact sequences with very minimal dialogue. The narrative largely revolves around a dad (played by Hugh Jackman) whose six-year old daughter goes missing. Then there’s the determined detective Loki (Jake Gyllenhaal) who is tasked with the job of finding the missing girls.

The dad’s resilience and the detective’s persistence take them in their own paths to arrive at the truth. And in this one perfect shot, Deakins and Villeneuve hint that these two characters’ path could finally converge. Throughout Prisoners, Deakins pushes the boundaries of lighting to create an oppressive, moody atmosphere. The medium shot of silhouetted-Loki standing amidst the ashy snowflakes with a crime scene light in the background remains emblematic of the narrative’s atmosphere of dread and tension.

18. The Dusk Raid, Sicario (2015)

Roger Deakins returned to the rugged, isolated desert landscape in Denis Villeneuve’s drug-cartel drama which was last seen in Coen Brothers’ No Country for Old Men (2007) and True Grit (2010). Deakins-Villeneuve duo’s talent for crafting tense sequences are evident in the early raid scene through the dangerous streets of Mexico City. However, the most challenging sequence in Sicario is when the black-ops soldiers get ready for the upcoming fight in the desert as the sunset looms over them. It gives an eerie, otherworldliness to the moment as we see a fading orange light in the distance.

This audacious composition was shot over two days, waiting for the 30-40 minutes window between dusk and darkness. No other lights were used. Moreover, the brilliance of this scene lies in how the continuity is maintained. Deakins mentions that with Sicario he went with the ‘less is more’ mantra. He also considers the framing and lighting in Jean-Pierre Melville’s movies as a notable influence for Sicario’s aesthetic style.

19. Hello Handsome, Blade Runner 2049 (2017)

After 13 Oscar nominations, Roger Deakins received his first Oscar for Denis Villeneuve’s sci-fi psychodrama. This was the third collaboration between Deakins and Villeneuve. And the duo offers a plethora of hypnotizing imagery that makes the movie experience almost transcendental. The heavily textured, film-noir inspired cinematography is omnipresent, since Blade Runner 2049 is set in a dystopian world of smoke, dust motes, and rain. There are a lot of stunning landscape shots. But one brilliantly trippy shot in the movie is when Ryan Gosling’s Officer K, towards the end, looks at a giant pink hologram of a nude woman.

The profound sadness in this scene is delicately portrayed through simple glances and a rich atmosphere. Though visual effects wizardry is involved in the scene, the atmosphere was largely made up of actual light and colors. The ‘Pink Joi’ was shot first, and they used 40*30 LED screens to play back the image of ‘Joi’. In fact, the pink and blue color in the ad was the primary light source for the whole shot. Visual effects department worked to make ‘Joi’ look more three-dimensional and to project her out of the giant screen.

Watch: Blade Runner 2049 Explained

20. Night Combat, 1917 (2019)

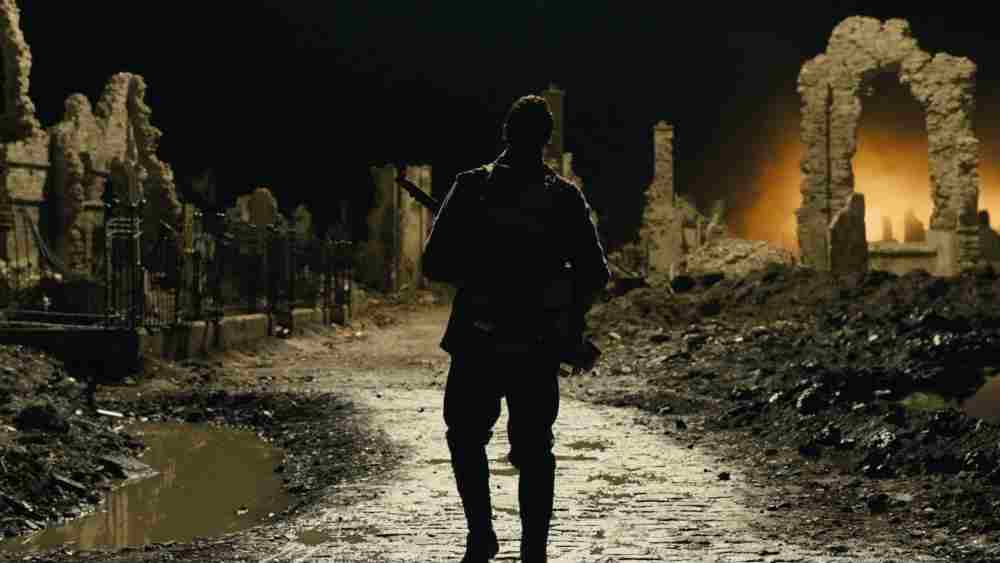

Making a movie look like it’s one continuous shot is not new in cinema. There are quite a few examples such as Birdman (2014), Son of Saul (2015), etc. But Sam Mendes’ 1917 is a World War I film, set in a battlefront full of gripping action sequences and explosions. Prior to 1917, Deakins hadn’t worked in many war or action movies. However, the cinematographer dazzlingly pulls it off, maintaining an atmosphere of dread and tension throughout the narrative. The precise and dynamic camerawork captures a range of human emotions in a devastating scenario.

The most standout sequence in 1917 is the night-time movement of Lance Corporal Schofield through the city of dilapidated buildings. Deakins once again proves he is a master of night cinematography, using light from overhead blast and flares, alongside a pool of shadows to create a moment of surrealistic horror. The flares flying were said to be suspended on wires in order to control the shadow’s direction. As usual Deakins planned the camera moves in the shot by first building a model of the cityscape. The ace cinematographer deservingly won his second Oscar for 1917.

Conclusion

Roger Deakins recently released a book titled Byways, a compendium of black-and-white photos from his private collection. Deakins has also reunited with Sam Mendes to work on a romance drama titled Empire Lights. Although one of the most lionized cinematographers in the industry, Deakins maintains some level of contact with young filmmakers and fans. He has set up a forum on his personal website rogerdeakins.com to answer any questions related to cinematography or filmmaking. The forum also serves as a space for amateur filmmakers to talk about their shooting strategies.

Despite the advancement of digital technology, Roger Deakins often reiterates that technology is merely a tool which can perfectly assist a filmmaker but tools don’t make a film. And as long as there are masters like Deakins behind the lens, there would be no dearth of dazzling imagery.

What are your favorite Deakins’ shots that are not mentioned in the list above? Let us know in the comments below.